EU Drug Market: Heroin and other opioids — Trafficking and supply

This resource is part of EU Drug Market: Heroin and other opioids — In-depth analysis by the EMCDDA and Europol.

Heroin trafficking to Europe

The overall number of heroin seizures in Europe fell by about 40 % between 2011 and 2021. However, this decline is registered from a relatively high baseline, as in 2011 the number of seizures reported in the EU was at its highest level recorded (31 133). The number of seizures remained largely stable until around 2015 (28 180), gradually declining thereafter and reaching 18 709 in 2021. This decline in the number of seizures may be due to a number of factors, one of which is a deprioritisation of law enforcement actions against retail-level interdiction.

In 2020, there was a stable number of heroin seizures but a considerable drop in the quantities seized, reflecting a temporary reduction in trafficking and a reprioritisation of law enforcement activities during the COVID-19 crisis. The quantity seized has since rebounded, following the easing of COVID-19 restrictions (see Figure Number of heroin seizures in the EU, Türkiye and Norway, 2011-2021).

Despite the marked decline in the number of seizures between 2011 and 2021, the quantities of heroin seized in the EU more than doubled in this period (from 4.2 tonnes in 2011 to 9.5 tonnes in 2021). This indicates that large quantities of heroin are trafficked in individual shipments and reflects a reprioritisation of wholesale-level rather than retail-level interdiction.

Over 9.5 tonnes of heroin was seized in the EU in 2021, representing the highest annual quantity seized over the past two decades. Furthermore, a record quantity of 22.2 tonnes of heroin was seized in Türkiye in 2021, bringing the overall quantity of heroin seized in the EU, Türkiye and Norway to 31.8 tonnes that year (see Figure Quantity of heroin seized in the EU, Türkiye and Norway, 2011-2021). Based on preliminary information, Türkiye seized only 7.9 tonnes of heroin in 2022.

The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Despite the significant quantities of heroin seized in 2021, and the much larger quantities seized in individual shipments than in the past, heroin has become on average 20 % more affordable on the EU market since 2015. This suggests that large quantities of the drug are still reaching consumer markets.

Heroin trafficking routes to Europe

Historically, the trafficking of heroin to the EU from Afghanistan and neighbouring countries – Iran and Pakistan in particular – has been concentrated along a few established routes. However, the intensity of use of particular routes has varied over time and the combinations of routes used by traffickers appears to be increasing. This is driven by a range of factors, such as geopolitical, social and economic conditions, including the level of perceived or actual risk of interdiction along the routes, the volume of migration flows, the state of the transportation infrastructure, the level of corruption vulnerability and market size. Transhipment points in key locations, such as Türkiye and the UAE, are also increasingly a feature of heroin trafficking to Europe, generating additional challenges for law enforcement (see Box Key transhipment points for heroin trafficking).

Four routes are commonly documented for heroin trafficking from Afghanistan to Europe (see Figure Indicative heroin trafficking routes):

- Balkan route – historically considered to be the main established trafficking route to Europe from Afghanistan via Iran and Pakistan to Türkiye and then through Bulgaria, Greece or the Mediterranean Sea,

- Southern route – through Iran or Pakistan, either transiting the East African coast or the Arabian Peninsula, towards Europe,

- Caucasus route – from Afghanistan through Iran to Armenia or Azerbaijan to Georgia and then through the Black Sea to Bulgaria, Romania or Ukraine,

- Northern route – from Afghanistan to Tajikistan and then through Kyrgyzstan or Uzbekistan to Kazakhstan, on to Russia and Ukraine and then to EU Member States (particularly the Baltic countries and Poland).

Since late 2021, two major political and security changes have occurred that have implications for the production and trafficking of opiates to Europe. The collapse of the Afghan government and the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021 and the subsequent ban on opium cultivation announced in April 2022 may significantly influence the production of opiates in Afghanistan and, by extension, the availability of heroin on the EU market (see Section Key developments in the opiate trade in Afghanistan). In addition, Russia’s war on Ukraine, which began in February 2022, has the potential to disrupt heroin trafficking through Central Asia and the Caucasus and through the Black Sea to Europe (see Box Implications of Russia’s war on Ukraine on heroin trafficking to the EU market).

Balkan route

The Balkan route from Afghanistan through Iran, Türkiye and the Balkan countries represents the shortest and most direct route to European consumer markets. On this route, heroin usually enters the EU at land border crossing points in Bulgaria or Greece. This is an established corridor for the trafficking of heroin to the EU and of acetic anhydride in the opposite direction (see Section Acetic anhydride: the key chemical used for the production of heroin). Law enforcement information identifies Iran as a significant hub for the trafficking of heroin along the Balkan route (see Box Seizures of opium, morphine and heroin in Iran and Pakistan), where large quantities of the drug are concealed, including incorporated in legal cargo and hidden in vehicles, before onward trafficking to the EU via Türkiye.

Bordering two EU Member States, Türkiye is another key country on the Balkan route. Although heroin seizures decreased during the COVID-19 crisis, Türkiye continued to seize significant quantities of heroin, reporting a record 22.2 tonnes in 2021 (see Figures Opium, morphine and heroin seizures in Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan and Türkiye, 2017-2021). Preliminary data for 2022, however, indicate a sharp drop to 7.9 tonnes.

From Türkiye, heroin is shipped to the EU along three branches of the Balkan route:

- southern branch – overland through Greece and Albania or using maritime methods through the Mediterranean Sea,

- central branch – through Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia, and into Italy or Austria, essentially by land,

- northern branch – a land route from Bulgaria to Romania and from there directly to consumer markets in the central and western EU.

A proportion of the heroin smuggled along the southern and central branches may be diverted for local consumption or temporarily stored in warehouses in the Western Balkans region, before being transported to the EU markets (EMCDDA, 2022a).

As a gateway to the EU, Bulgaria is particularly important for this trafficking route. Until recently, law enforcement authorities have regularly reported sizeable amounts of heroin at border crossing points, particularly at the Kapitan Andreevo crossing (National Customs Agency of the Republic of Bulgaria, 2019a,b, 2020a,b, 2021b-d). In 2021, the National Customs Agency in Bulgaria reported 10 seizures amounting to 1 134 kilograms. This represents a 350 % increase from the 251 kilograms reported in six seizures in 2020, although seizures were probably low that year due to measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, reports from the National Customs Agency indicate an 80 % reduction in the quantity of heroin seized in 2022, amounting to 223 kilograms in 10 seizures (National Customs Agency of the Republic of Bulgaria, 2023, communication to the EMCDDA).

Possible shift of the Balkan route southward, exploiting maritime methods

In addition to using the established land entry points to the EU, trafficking groups appear to be increasingly transporting heroin to Turkish ports on the Mediterranean Sea, where ferries and cargo vessels carry the consignments onward to EU ports in Croatia, Italy and Slovenia. It is likely that a number of other European ports with direct links to Türkiye will also be targeted.

In October 2021, Croatian police seized 220 kilograms of heroin in the southern Adriatic port of Ploce, concealed in a cargo of lead ingots on a ship arriving via Türkiye (see Table Examples of large maritime heroin seizures in the EU, 2019-2022). The apparent reasons for the shift to trafficking via maritime transportation include a lower perceived risk and the increased cost-effectiveness of this modus operandi, particularly for large shipments. A likely contributor to this shift is the exploitation of commercial transportation from Türkiye, which is frequently intramodal and combines land and sea elements, such as lorries transported on ferries across the Mediterranean Sea to ports in the EU. Exploiting this existing intramodal shipping infrastructure allows traffickers to smuggle larger quantities of heroin in single shipments than they could in the historical modus operandi of moving smaller consignments through concealment in vehicles on other land routes. This apparent recent shift in trafficking also increases the complexity of monitoring and disrupting illicit heroin flows to the EU.

Southern route

Over the past decade, the importance of the Southern route for the EU heroin market has grown. This can be seen in the large quantities of heroin departing from ports on the Iranian or Pakistani sides of the Makran Coast, such as Chabahar and Bandar Abbas (Iran) and Gwadar (Pakistan). These heroin consignments are either transported by traditional sailing vessels (dhows) or, increasingly, concealed in maritime containers from commercial ports. Overall, a range of modi operandi and transhipment points are combined on the Southern route to smuggle heroin to Europe.

The growing importance of the Southern route is driven by several factors. First, increased use of maritime containers allows more efficient transportation of large quantities of heroin. The main commercial maritime routes from east to west are exploited for these purposes. In addition, intensified trafficking along the Southern route may be due to the perception or reality of stricter border controls on the Balkan route. Finally, the increasing use of multiple transhipment points for containers along the Southern route potentially makes it more difficult for authorities to make interceptions based on the analysis of a shipment’s origin, reducing the risk of interdiction to traffickers (see Box Comparison of heroin markups on selected European wholesale markets and Box Key transhipment points for heroin trafficking).

The Netherlands continues to be a hub for the consolidation and distribution of heroin for EU consumer markets, including for maritime heroin consignments trafficked along the Southern route (see Section Heroin trafficking within the EU). Similar to other drugs, heroin shipments are stored in distribution and wholesale centres in the Netherlands before being broken down and smuggled to criminal networks that supply other EU Member States and the United Kingdom (see Box Transhipment of heroin in containerised shipments to the United Kingdom).

Heroin may be shipped to the EU using the various branches of the Southern route, all departing from Iran or Pakistan.

- The first branch transits the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea, through the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean Sea, mainly reaching ports in the EU or Türkiye in shipping containers.

- The second branch of this route uses free trade ports in the Arabian Peninsula as transhipment points. For example, heroin can be offloaded in the UAE, from where it can be shipped overland or by sea to EU countries.

- A third branch departs from smaller ports on the Makran Coast to ports in Africa along the Swahili coast (Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique) and South Africa. From there, the heroin may be smuggled inland for domestic consumption or for onward trafficking to the EU and other international markets. A recent development in this branch appears to be the combined trafficking of methamphetamine with heroin (GITOC, 2021).

The first branch of the Southern route appears to have seen increased activity since 2021, facilitating containerised trafficking of large consignments of heroin to the EU. This can be seen in a number of large heroin seizures shipped in maritime containers, originating from ports in Iran and Pakistan and bound for the European market (see Box Large-scale direct heroin shipments to European ports). While the ratio of consignments that are successfully delivered to those that are seized is unknown, this development presents a clear threat of increased access to heroin in Europe.

Large shipments of heroin along the second branch of the Southern route have also been observed (see Table Examples of large maritime heroin seizures in the EU, 2019-2022). Since 2021, Bulgaria and Romania have reported seizing large consignments of heroin originating from Iran, via the UAE, bound for Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands or Romania (see Box Large-scale heroin shipments to European ports via the UAE). Based on the available information, the UAE in particular appears to have emerged as a hub for heroin transhipment to Europe, and possibly a storage point where the origin of the drugs may be obscured. Seizures indicate that heroin consignments trafficked from key source countries on one route are in some cases switched to another route at transhipment points. This provides greater flexibility for traffickers and allows them to exploit new opportunities.

| Date | Country | Port of seizure | Weight (kilograms) | Route | Concealment | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

August 2022 |

Germany |

Hamburg |

700 |

Iran-Germany |

BKA (2022) |

|

|

May 2022 |

Netherlands |

Rotterdam |

2600 |

Sierra Leone-Morocco-Netherlands |

Soap |

The Netherlands, Openbaar Ministerie (2022) |

|

October 2021 |

Croatia |

Ploce |

220 |

Iraq-Türkiye -Croatia-Belgium (controlled delivery) |

Lead ingots |

Scaturro and Kemp (2022) |

|

June 2021 |

Slovenia |

Koper |

200 |

Iran-Slovenia |

Scaturro and Kemp (2022) |

|

|

May 2021 |

Bulgaria |

Varna-West |

530 |

Iran-UAE-Bulgaria-Netherlands (controlled delivery) |

Marble tiles |

National Customs Agency of the Republic of Bulgaria (communication to the EMCDDA) |

|

May 2021 |

Romania |

Constanta |

1452 |

Iran-UAE-Romania-Belgium-Netherlands (controlled delivery) |

Marble tiles |

Europol (2021b) |

|

February 2021 |

Bulgaria |

Varna-West |

401 |

Iran-UAE-Bulgaria-Belgium (controlled delivery) |

Bitumen rolls |

National Customs Agency of the Republic of Bulgaria (2021a) |

|

February 2021 |

Netherlands |

Rotterdam |

1500 |

Pakistan-Netherlands |

Himalayan salt |

Openbaar Ministerie (2021b) |

|

December 2019 |

Netherlands |

Rotterdam |

439 |

Pakistan-Netherlands |

Talc stone |

Dutch police communication to Europol (2020) |

|

October 2019 |

Slovenia |

Koper |

730 |

UAE-Egypt-Slovenia |

Polyethylene foil |

Republic of Slovenia Ministry of the Interior (2019) |

Heroin trafficked along the third branch of the Southern route departs from the Makran Coast, typically in dhows, and is unloaded in several countries along the east coast of Africa. From there, the drugs are transported overland to South Africa or to other countries in East or West Africa. However, it appears that heroin is also increasingly being transported in container ships, which, unlike the dhows, can sail directly from the Makran Coast to South Africa. From there, South Africa’s extensive international transport links can be used to smuggle the drugs to Europe by air or sea. In addition, some of the drugs trafficked along this route are destined for local consumption, owing to sustained demand for heroin and other opioids in some African countries (Cousins, 2022; Harker et al., 2020; Hunter, 2021).

This established heroin trafficking route appears to be increasingly exploited for the co-trafficking of methamphetamine to global markets, including the EU (GITOC, 2021). This may be due to the recent surge in methamphetamine production in Afghanistan (see Methamphetamine module). Routes used for further transportation from the East African coast to other countries in Africa and to Europe are complex. While information on these is lacking, an analysis of available data from heroin seizures occurring in EU countries between 2018 and 2021 highlights that Ethiopia, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa are significant transit countries (see Figure Non-EU countries identified as the ‘origin’ or ‘transit’ of heroin seized in the EU, 2018-2021).

Note: This graph is based on the frequency of reports and not on heroin seizure quantities. Given that the data are incomplete, this graph does not present a ranking of countries. Countries are colour-coded within the following world regions: Asia, Europe, Middle East, East Africa, West Africa, Southern Africa. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

There is also evidence of large quantities of heroin arriving in the EU from countries in Africa by sea. In May 2022, 2.6 tonnes of heroin was seized from a container loaded with soap arriving at Rotterdam port and originating from Sierra Leone (Openbaar Ministerie, 2022). Other methods employed to bring heroin from Africa to the EU include postal and parcel services and the use of air passengers as drug couriers. According to 2018-2021 data from the World Customs Organization Regional Intelligence Liaison Office, Western Europe (RILO-WE), South Africa remained the main distributor of heroin in mail consignments or by drug couriers at airports from the African continent, followed by Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, Tanzania and Mozambique (WCO RILO-WE, 2023) (see Box Heroin trafficked from Africa by air couriers and the section Fluidity of routes, methods of transportation and modi operandi). Due to COVID-19-related travel restrictions in the first months of 2020, heroin trafficking by air passengers was heavily curtailed (EMCDDA and Europol, 2020).

Caucasus route

The Caucasus route usually involves heroin being smuggled on ferries across the Black Sea from Georgia to Bulgaria, Romania and, until recently, Ukraine (US Embassy Tbilisi, 2021). Several large heroin seizures on this route in recent years confirm that it is used to smuggle large amounts of opiates from Iran to Europe via Armenia or Azerbaijan and Georgia (Customs.gov.az, 2021; EMCDDA and Europol, 2020; Jalilov, 2021).

A number of recent seizures in Azerbaijan have involved heroin trafficked in trucks with legal goods from Iran. Several of these seizures between 2020 and 2021 involved several hundred litres of heroin in liquid form, typically concealed in fuel tanks of vehicles and intended for countries in Eastern Europe, the Baltic region, Türkiye and Western Europe. Iranian authorities also routinely report seizures of heroin in liquid form near the borders with Afghanistan and Pakistan, some of which appear to have been intended for onward trafficking (IRNA, 2022). This phenomenon warrants awareness, including in the EU, where heroin seizures in liquid form have not been reported.

Until Russia’s war of aggression, Ukraine was an important storage and transhipment point for heroin on the Caucasus route, providing access to lucrative markets in both Western Europe and Russia by a variety of overland routes. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, however, has changed the trafficking landscape in the region. The insecurity on the ground in Ukraine and the disruption to maritime trade in the Black Sea have diminished the practicality of trafficking via Ukraine and are likely to lead to further diversion of maritime trafficking to other ports in the Black Sea or the Mediterranean (see Box Implications of Russia’s war on Ukraine on heroin trafficking to the EU market).

Northern route

The Northern route has historically been used to smuggle heroin by land from Afghanistan’s northern borders into Tajikistan and then northwards through Kyrgyzstan or Uzbekistan to Kazakhstan before entering Russia (UNODC, 2018). Heroin trafficked on this route appears to be destined mainly for consumer markets in Central Asia, Belarus, Russia and Ukraine (Bobokhodzhiev, 2022). Significant heroin seizures have recently been reported by countries along the Northern route, such as 440 kilograms seized by Kyrgyzstan in 2021. This suggests that criminal networks active on this route may be able to smuggle large quantities of heroin towards consumer markets in Russia and beyond (Kadyrov, 2021).

EU Member States rarely seize heroin trafficked via the Northern route. Nonetheless, a proportion of the heroin shipped on the Northern route may eventually enter the EU from Russia and through Poland and the Baltic countries, and from Ukraine to Hungary, Romania and Slovakia. Some heroin seized in Belarus, Romania and Ukraine in recent years was reported as having originated from Central Asia and being intended for Western European markets. However, Russia’s war on Ukraine is likely to diminish the opportunities for heroin trafficking to the EU on this route (see Box Implications of Russia’s war on Ukraine on heroin trafficking to the EU market).

Fluidity of routes, methods of transportation and modi operandi

The analysis shows that large heroin consignments arrive in the EU through various entry points and that the established trafficking routes are flexible and fluid, as are the methods of transportation and concealment. An example of this is the growing practice of combining trafficking routes, whereby criminal networks move heroin consignments from one means of transport to another at transhipment points (see Box Key transhipment points for heroin trafficking).

When heroin is trafficked by land, it is typically hidden in concealed compartments or among legal goods. While typically trafficked in powder form, traffickers also dissolve heroin in liquids to conceal it and minimise the risk of checks.

In recent years, heroin trafficking by maritime routes appears to have increased (see Section Southern route). This is believed to be one of the strategies adopted by traffickers to overcome the restrictions implemented as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (EMCDDA and Europol, 2020). Roll-on roll-off ferries and pleasure boats also appear to be used in some places, although this method is not well understood. One of the most frequently used methods for trafficking heroin by sea involves concealment in maritime containers and among legal goods through the use of fake labelling, documentation or packaging.

Heroin is also trafficked by air, albeit in smaller quantities than in other modes of transport. While limited data are available on trafficking using private aircraft, heroin is regularly trafficked to Europe by couriers travelling on commercial flights from African countries (see Box Heroin trafficked from Africa by air couriers).

Another method employed to bring heroin into the EU is through mail consignments. The online trade relies heavily on post and parcel shipping, including through express courier services, and criminals take advantage of the large volume of parcels passing through mail distribution centres. As in the case of other drugs, criminals exploit the services of parcel delivery providers operating across the world to smuggle heroin. While the data available are limited, there is evidence of heroin trafficking through the postal system both within and to the EU from Africa and the Middle East (see Box Heroin trafficked through mail consignments).

Factors influencing trafficking routes and modi operandi

Trafficking routes connect heroin production and consumer markets in the EU and may vary over time due to various factors. Importantly, criminal networks seek to maximise profits while minimising costs (see Box Comparison of heroin markups on selected European wholesale markets). Based on the present analysis, three factors of particular importance emerge.

First, globalisation has facilitated rapid connection and transportation between heroin production and consumer markets. Continuing international developments in transport infrastructure, such as the Chinese-led Belt and Road Initiative, courier services and containerised shipping, offer a range of new opportunities to traffickers to conceal heroin consignments while hampering the efforts of law enforcement. Ongoing developments in this area can influence changes in the relative preference for different routes.

Second, changes in law enforcement activity and the availability and use of new sources of information on criminal activity, such as intercepting encrypted communications, may cause traffickers to adapt their modi operandi. Overall, law enforcement knowledge on heroin trafficking has improved considerably over recent years, with information being obtained from the lawful interception of encrypted communication platforms, such as Sky ECC. However, decryption and the translation and analysis of information present an ongoing challenge for law enforcement in the EU. It is also important to note that changes in law enforcement approaches and priorities may result in the discovery of trafficking routes and methods that have been in existence for some time rather than newly established routes and methods.

Third, unexpected events, such as global crises, instability and armed conflicts, and significant political or economic changes, may affect drug trafficking. Criminal networks will strive to adapt to these events, both to overcome any difficulties they create and to exploit opportunities they present. Recent shocks include the COVID-19 pandemic, the Taliban’s rise to power in Afghanistan (see Section Key developments in the opiate trade in Afghanistan) and Russia’s war on Ukraine (see Box Implications of Russia’s war on Ukraine on heroin trafficking to the EU market). For example, armed conflicts often lead to the displacement of populations and a breakdown of social structures, which can lead to vulnerable populations becoming more susceptible to exploitation for drug trafficking or use. Understanding how drug trafficking continuously adapts to global or regional crises can help to anticipate changes in trafficking patterns.

Heroin trafficking within the EU

Once smuggled into the EU, heroin is then distributed to consumer markets across Europe. The Netherlands and, to a lesser extent, Belgium, Bulgaria, France and Germany remain important hubs for intra-EU heroin trafficking. These countries are most frequently reported as origin or transit points for heroin shipments seized in other EU Member States (see Figure EU countries identified as the ‘origin’ or ‘transit’ of heroin seized in the EU, 2018-2021). This is supported by data reported to the WCO RILO-WE (2023) (see Box Intra-EU heroin distribution).

Recent data suggest that the role of heroin remains important in a number of EU Member States, including Italy, France, Spain and Germany. Therefore, large quantities of heroin are likely to be trafficked to these countries to meet local demand.

Consumer markets for heroin appear to remain stable, with only limited fluctuation in the number of users in the short term. However, there are several caveats that might suggest that recent changes in heroin use are not fully captured in current monitoring systems (see Section The consumer market).

Note: This graph is based on the frequency of reports and not on heroin seizure quantities. Given that the data are incomplete, this graph does not present a ranking of countries. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Synthetic opioid trafficking

The market for illicit synthetic opioids in the EU is supplied by both medicines (intended for therapeutic purposes) diverted from the legal market and a broad range of illicitly manufactured opioids.

Synthetic opioids intended for therapeutic purposes enter the illicit drug supply chain in a number of ways. For example, they may be stolen or diverted from the legitimate supply chain (including from manufacturers, wholesalers and pharmacies); from healthcare systems (from hospitals or through corrupt healthcare professionals or forged prescriptions); or from licit use (stolen directly from patients or when users sell or give away a proportion of their prescribed opioids).

The illicit production of synthetic opioids in the EU remains uncommon (see Section Synthetic opioid production in Europe: a marginal phenomenon). Generally, synthetic opioids are produced outside the EU and enter Europe through key logistics hubs. Typically, producers and traffickers of these substances ship small quantities anonymously through freight forwarders and postal or express courier services. Darknet markets, e-commerce and social media platforms are also exploited by sellers.

Because of their potential presence in very small quantities, synthetic opioids may be difficult to detect using routine analytical methods and techniques currently employed by forensic laboratories. Another issue is the emergence of new synthetic opioids that are not controlled by international drug control agreements, as these may also pose particular difficulties in terms of detection (see Box Detections and seizures of new synthetic opioids). This therefore remains an area requiring vigilance and some precautionary measures.

Falsified or counterfeit opioid-containing medicines are a growing cause for concern as they are associated with high public health risks. Falsified medicines contain different quantities of the active substances than claimed, or different active substances entirely. Counterfeit medicines have the composition that is claimed but they infringe trademark rules (European Medicines Agency, n.d.). Overall, more information is needed on the diverse sources of these medicines. To gain a better understanding of this situation would require both forensic analysis of reported seizures to determine their source, and consistent reporting of the number of seizures and quantities seized.

Based on reports to the EMCDDA from the Reitox national focal points, which do not necessarily contain results from forensic analyses, it has been possible to analyse seizures of some synthetic opioids in the EU. However, the number of reporting countries has varied from year to year, limiting the comparability of results (see Table Seizures of selected synthetic opioids in the EU, 2018-2021).

| Year | Number of seizures (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in kilograms (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in litres (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in tablets (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in patches (number of reporting countries) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2018 |

1 018 (17) |

130.9 (9) |

26.2 (7) |

7 527 (8) |

- |

|

2019 |

1 001 (16) |

18.1 (9) |

42.8 (10) |

6 374 (10) |

- |

|

2020 |

1 068 (18) |

59.7 (11) |

20.9 (10) |

5 849 (10) |

- |

|

2021 |

888 (19) |

251.7 (12) |

29.9 (11) |

6 802 (7) |

- |

| Year | Number of seizures (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in kilograms (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in litres (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in tablets (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in patches (number of reporting countries) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2018 |

1 962 (15) |

0.2 (5) |

- |

96 340 (13) |

- |

|

2019 |

2 153 (15) |

0.3 (5) |

- |

119 864 (12) |

- |

|

2020 |

2 354 (16) |

0.3 (11) |

- |

192 532 (11) |

- |

|

2021 |

1 710 (15) |

5.0 (5) |

- |

110 787 (12) |

- |

| Year | Number of seizures (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in kilograms (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in litres (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in tablets (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in patches (number of reporting countries) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2018 |

5 214 (12) |

0.7 (4) |

- |

1 142 347 (9) |

- |

|

2019 |

4 422 (12) |

0.05 (2) |

- |

1 577 309 (9) |

- |

|

2020 |

4 305 (12) |

0.3 (4) |

- |

1 051 969 (10) |

- |

|

2021 |

4 515 (9) |

0.3 (4) |

- |

2 228 466 (7) |

- |

| Year | Number of seizures (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in kilograms (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in litres (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in tablets (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in patches (number of reporting countries) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2018 |

645 (8) |

0.02 (3) |

- |

15 216 (7) |

- |

|

2019 |

677 (9) |

0.02 (1) |

- |

23 870 (10) |

- |

|

2020 |

866 (10) |

0.8 (4) |

- |

43 654 (9) |

- |

|

2021 |

814 (9) |

0.1 (3) |

- |

66 721 (8) |

- |

| Year | Number of seizures (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in kilograms (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in litres (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in tablets (number of reporting countries) | Quantity in patches (number of reporting countries) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2018 |

853 (11) |

6.2 (11) |

- |

19 795 (5) |

587 (2) |

|

2019 |

394 (13) |

15.1 (9) |

- |

320 (4) |

363 (3) |

|

2020 |

387 (14) |

11.1 (11) |

- |

91 (5) |

341 (3) |

|

2021 |

174 (11) |

5.5 (8) |

- |

5 444 (5) |

168 (4) |

Fentanyl and its derivatives

The trafficking of fentanyl and its derivatives, such as carfentanil, is a particular concern for the EU. These extremely potent substances have high associated morbidity and mortality, posing serious and complex public health and law enforcement challenges. Information made available to Europol indicates that parcels containing fentanyl, some of which were connected to sales on darknet markets, have been sent to the EU from the United States. Although the problem of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids in the EU is much less severe than the opioid crisis in North America, the high potency of some of these substances means that small-scale suppliers can have a significant harmful impact.

As with other synthetic opioids, fentanyl derivatives are produced mainly in clandestine laboratories outside the EU. Their distribution, primarily to the Baltic and Nordic countries, occurs in two strands. In one strand, fentanyl derivatives are distributed by criminal networks operating in EU destination countries, although there is an intelligence gap regarding their composition and nationalities. In the other strand, they are purchased directly by consumers and retail-level distributors via online platforms on the surface web and the darknet. On the Estonian market, fentanyl has replaced heroin as the main opioid consumed since 2001. An increase in the availability of fentanyl derivatives was also seen in neighbouring markets, especially Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden, until around 2018, after which it declined.

New fentanyl derivatives not covered by fentanyl controls were also detected in Europe in 2022 and 2023. New non-fentanyl synthetic opioids, including benzimidazole (nitazene) opioids, have also appeared on the drug market in the EU, posing concerns. Isotonitazene has been detected on the market in Latvia and Estonia, substituting for other opioids that are in short supply (LSM.lv, 2020; Nra.lv, 2021).

Seizure trends in fentanyl derivatives

Ten EU Member States consistently provide seizure data on fentanyl derivatives. They reported a drop of just over 60 % in the number of seizures between 2018 and 2021. The three countries that accounted for the vast majority (95 %) of the seizures in 2018 (Estonia, Latvia and Sweden) reported a decrease of 67 % on average (from 432 seizures in 2018 to 144 in 2021). Only Austria reported an increase, from four seizures in 2018 to 11 in 2021 (see Figure Number of seizures of fentanyl derivatives in 10 EU Member States, 2018-2021). However, due to the low number of seizures, caution should be exercised in interpreting this increase.

Note: * ‘Other’ comprises Czechia, Greece, Italy, Romania, Slovakia, Spain. Annual reports of the Reitox national focal points to the EMCDDA Fonte data collection tool. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

While the data give strong evidence of a decrease in the number of seizures of fentanyl derivatives, less data are available to draw firm conclusions regarding quantities seized (see Table Seizures of selected synthetic opioids in the EU, 2018-2021). Although the quantity reported by weight seized in 2021 was lower than in previous years, a wide range of fentanyl derivatives were reported to have been seized. This included carfentanil in combined seizures with fentanyl, and sometimes with methadone (reported by Latvia in 2020 and Lithuania in 2021), and remifentanil and alfentanil (reported to have been seized in Slovakia in 2021). Furthermore, following a significant drop in the reported number of tablets seized, from 19 795 in 2018 (five reporting countries) to 91 in 2020 (four reporting countries), the number rose to 5 444 in 2021 (five reporting countries). These changes in the reported number of tablets seized were almost exclusively driven by Sweden. The country accounted for the bulk (99 %, 5 374 tablets) of the fentanyl-derivative-containing tablets reported to have been seized in the EU in 2021, a pattern also observed in previous years.

The overall decline in the number of seizures of fentanyl derivatives is probably driven by two key factors. These are the targeting, both offline and online, of fentanyl derivative distribution networks by law enforcement in affected EU Member States and controls placed on new psychoactive substances in China.

For example, since 2018, Sweden has limited the availability of fentanyl derivatives online as a result of successful operational measures taken by the Swedish Police Authority and the work of the Public Health Agency of Sweden (EMCDDA and Europol, 2019). The number of reported seizures in the country fell by 70 % between 2018 (80) and 2021 (23). Other European countries have systematically targeted criminal networks involved in the distribution of these substances. In Estonia, this probably contributed to the 90 % decrease in the number of seizures between 2018 (198) and 2021 (16). A sharp decline in the purity of ‘street’ fentanyl was also documented in Estonia, from a range of 17-86 % (mode 13 %) in 2017 to record low purities of 1.5-22 % (mode 2.8 %) in 2018 (Estonian Forensic Science Institute, 2019, as cited in Uusküla et al., 2021).

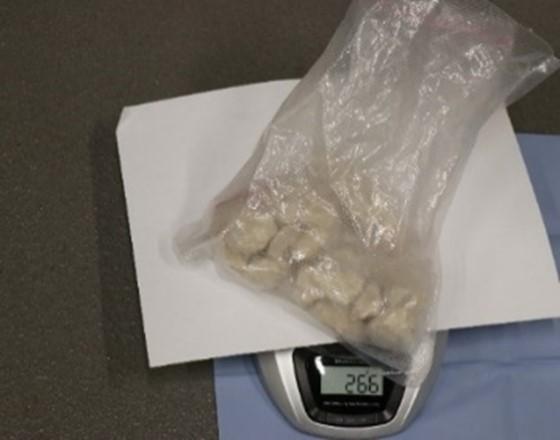

Despite the notable decrease in the number of seizures in the 10 EU Member States that consistently provided data between 2018 and 2021, there is evidence of continued trafficking of fentanyl derivatives. For example, Estonian police reported the seizures of 266 grams and 570 grams of carfentanil in two operations near the Latvian border in April and May 2022, respectively. The drugs were trafficked from Latvia by Latvian nationals, allegedly for distribution on the Estonian market (see Photos Carfentanil seized in two operations in Estonia, April and May 2022).

Efforts at national level have been boosted by the generic control measures on fentanyl derivatives imposed in 2019 in China, historically one of the main source countries for new psychoactive substances. This measure covers the illicit production, export and sale of all fentanyl derivatives. In 2021, the INCB noted that this legislation had led to a sharp drop in the quantity of fentanyl-related substances of alleged Chinese origin being seized globally (INCB, 2021a). However, traffickers and producers appear to have adapted by using new methods, such as the use of non-scheduled chemicals and chemically masked fentanyl precursors, to circumvent the ban (INCB, 2021a). The long-term impact of these developments on Europe needs to be monitored.

Opioid medicines

A number of other synthetic opioid medicines, including methadone, buprenorphine, tramadol and oxycodone, continue to be seized in the EU. In addition to illicit production both outside and inside the EU, medicinal products containing synthetic opioids are also diverted from legitimate supplies. Synthetic opioids are key active pharmaceutical ingredients in many medicines prescribed and sold in the EU and come in a variety of forms, including tablets, patches, sprays and lozenges. Fentanyl-containing medicines diverted from legal supply are most commonly seized as patches, sprays and lozenges (see Box Operation Chimera: diversion and trafficking of fentanyl and other opioids in Romania). In some countries, such as France, the diversion of opioid medicines, such as methadone and buprenorphine, is reported to be the main source for their illicit drug markets.

Some of the opioid medicines seized in the EU are intended for use outside the region. For example, seizures of tramadol reported in a number of EU countries appear to have been in transit to the Middle East and Africa. Despite high availability in the EU, tramadol currently has a low rate of misuse across European countries (with the possible exception of France; see Section Overdose deaths related to heroin and other opioids) (Iwanicki et al., 2020). This is in contrast to data from some countries in Africa and Middle East, where no other prescription opioids are available and where rates of non-medical tramadol use have been rising (UNODC, 2020; WHO, 2018).

Of concern is the recent increase in oxycodone seizures in the EU. Five EU Member States (Austria, Czechia, Italy, Latvia and Sweden) that consistently report data and accounted for most of the oxycodone seizures in 2018 (see Table Seizures of selected synthetic opioids in the EU, 2018-2021) reported a 52 % increase in the number of such seizures between 2018 and 2021 (from 528 to 801 seizures). Over the same period, these five countries reported a 373 % increase in the number of seized oxycodone tablets (from 14 010 to 66 205). Sweden was the main driver of the increase, accounting for 95 % of the seizures (772 out of 814 seizures) and 96 % of the tablets seized (64 126 out of 66 721 tablets) in 2021.

Developments have also been seen in the illicit buprenorphine trade. The misuse of buprenorphine in some EU Member States is considerable. For example, buprenorphine has been the main opioid misused in Finland for a number of years, with France being consistently reported as the source. It appears that relatively large buprenorphine shipments are moved from France via Germany, Sweden and Estonia to Finland. Eleven EU Member States consistently provide buprenorphine seizure data, and five countries accounted for 95 % of the seizures in 2018 (see Figure Number of buprenorphine seizures in 11 EU Member States, 2018-2021). Following an increase in the number of seizures between 2018 and 2020, a drop was noted in 2021. The decline was driven by fewer seizures reported by Austria, Finland, Greece and Sweden. In 2021, Latvia reported a 45 % increase in the number of buprenorphine seizures (from 205 in 2018 to 297 in 2021). However, this analysis is hampered by a lack of data from France and Germany (see Figure Number of buprenorphine seizures in 11 EU Member States, 2018-2021). In addition, Türkiye reported 1 144 seizures of buprenorphine in 2021, a 197 % increase on the 385 seizures reported in 2018.

Note: * ‘Other’ comprises Czechia, Italy, Croatia, Estonia, Romania, Portugal. Annual reports of the Reitox national focal points to the EMCDDA Fonte data collection tool. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Among the seven EU Member States that reported the quantity of buprenorphine tablets seized between 2018 and 2021, a 5 % increase was noted (see Table Seizures of selected synthetic opioids in the EU, 2018-2021). In addition, Türkiye reported increased buprenorphine seizures, from 10 123 tablets in 2018 to 16 662 tablets in 2021.

Fourteen EU Member States consistently provide methadone seizure data. Of the six countries accounting for the majority (86 %) of seizures in 2018, most reported fewer seizures in 2021 than in 2018. This influenced the overall decrease in methadone seizures of 16 % in this period (see Figure Number of methadone seizures in 14 EU Member States, 2018-2021).

Note: ‘Other’ comprises Austria, Croatia, Luxembourg, Ireland, Estonia, Latvia, Portugal, Hungary. Annual reports of the Reitox national focal points to the EMCDDA Fonte data collection tool. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Among six EU Member States (Estonia, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg and Spain) that consistently report the quantities of methadone seized, an increase of 1 267 % was noted (from 18 kilograms in 2018 to 246 kilograms in 2021). This large increase was driven mainly by seizures in Spain, where methadone seizures amounted to less than 10 kilograms per year between 2018 and 2020, but increased to 193 kilograms in 2021. The number of reported methadone tablets (or capsules) seized remained stable in this period, based on reporting from five EU Member States. Türkiye, however, reported a 50 % increase in methadone tablet (or capsule) seizures, from 26 908 in 2018 to 39 786 tablets in 2021.

Source data

| Number of seizures | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU, Türkiye and Norway | 35753 | 32266 | 33162 | 33897 | 41629 | 32659 | 36210 | 41812 | 36118 | 34337 | 34143 |

| EU27 | 31133 | 26849 | 25874 | 25595 | 28180 | 23482 | 22650 | 22733 | 19170 | 18499 | 18709 |

| Quantity seized (tonnes) | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU, Türkiye and Norway | 11.524 | 17.533 | 17.548 | 20.127 | 12.149 | 9.071 | 22.081 | 27.196 | 28.842 | 17.75 | 31.756 |

| EU27 | 4.217 | 4.188 | 4.013 | 7.327 | 3.793 | 3.472 | 4.597 | 9.335 | 8.589 | 4.35 | 9.522 |

| Non-EU country | Combined score |

|---|---|

| Ethiopia | 6 |

| Qatar | 4 |

| Türkiye | 3 |

| Uganda | 3 |

| Afghanistan | 2 |

| Iran | 2 |

| Pakistan | 2 |

| Switzerland | 2 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 2 |

| South Africa | 2 |

| Albania | 1 |

| Benin | 1 |

| Rwanda | 1 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 |

| Oman | 1 |

| Sudan Republic | 1 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1 |

| Zambia | 1 |

| Burundi | 1 |

| Kenya | 1 |

| Mozambique | 1 |

| Tanzania | 1 |

| Bahrain | 1 |

| Togo | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 1 |

| Armenia | 1 |

| China | 1 |

| Ghana | 1 |

| India | 1 |

| Malawi | 1 |

| Senegal | 1 |

| Country | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Spain | 1072 |

| Croatia | 802 |

| Italy | 658 |

| Romania | 633 |

| Netherlands | 362 |

| EU country | Combined score |

|---|---|

| Netherlands | 10 |

| France | 5 |

| Bulgaria | 4 |

| Germany | 4 |

| Belgium | 3 |

| Spain | 2 |

| Austria | 2 |

| Greece | 1 |

| Poland | 1 |

| Portugal | 1 |

| Romania | 1 |

| Luxembourg | 1 |

| Slovenia | 1 |

| Year | Other opioids | Fentanyl derivatives | Benzimidazoles |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 2013 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 2014 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 2015 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 2016 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| 2017 | 3 | 10 | 0 |

| 2018 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| 2019 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| 2020 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 2021 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 2022 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2023 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Country | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia | 198 | 70 | 20 | 16 |

| Latvia | 154 | 77 | 145 | 105 |

| Sweden | 80 | 52 | 37 | 23 |

| Austria | 4 | 5 | 24 | 11 |

| Other* | 17 | 31 | 24 | 18 |

| Country | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 908 | 1027 | 1190 | 839 |

| Finland | 328 | 396 | 324 | 231 |

| Greece | 301 | 292 | 311 | 133 |

| Latvia | 205 | 209 | 253 | 297 |

| Austria | 108 | 111 | 128 | 94 |

| Other* | 100 | 97 | 126 | 102 |

| Country | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 274 | 281 | 281 | 247 |

| Italy | 147 | 167 | 192 | 142 |

| Lithuania | 129 | 87 | 55 | 22 |

| Sweden | 119 | 147 | 149 | 114 |

| Romania | 87 | 84 | 92 | 93 |

| Greece | 70 | 74 | 85 | 77 |

| Other* | 130 | 138 | 148 | 115 |

References

Consult the list of references used in this module.