EU Drug Market: Heroin and other opioids — Retail markets

This resource is part of EU Drug Market: Heroin and other opioids — In-depth analysis by the EMCDDA and Europol.

The consumer market

In most countries in the EU, it appears that the number of people who use heroin is relatively stable. In 2021, the prevalence of high-risk opioid use among adults (aged 15 to 64) is estimated to be around 1 million. The countries estimated to have the highest number of users per 1 000 inhabitants aged 15 to 64 are Finland (at 7.7 users per 1 000 inhabitants), followed by Italy, Ireland, Austria and Denmark.

Heroin market size estimates

Conceptually, there are two main strategies for assessing the size of the drug market, namely a demand-based or bottom-up approach and a supply-side or a top-down approach. The strengths and limitations of these strategies are reviewed in a background paper (Udrisard et al., 2022).

A demand-based (bottom-up) approach

Using the methodology established by the EMCDDA (2019), it is possible to estimate the size of the heroin retail market based on the number of users and their use patterns, including how much they use per year and the average price paid at retail level. The EMCDDA collects data on the number of high-risk opioid users as part of routine monitoring efforts. While the overall prevalence of high-risk opioid use among adults (aged 15 to 64) in 2021 was estimated to be around 1 million people in the EU, there was considerable variation between countries, and whereas some countries specified the main opioid used, others did not. As such, for some countries an estimate is available for high-risk heroin users rather than for high-risk opioid users. This is the case for six countries: France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Slovakia and Spain. Where there is no estimate of high-risk heroin users available, this is imputed, based on high-risk opioid user estimates in combination with treatment data.

Using the latest available data, the minimum estimated annual retail value of the heroin market is EUR 5.2 billion (probable range EUR 4.1 billion to EUR 6.7 billion in 2021). Estimates of amounts used suggest that about 124 tonnes of heroin at retail-level purity (range 96.9 to 154.7 tonnes) was consumed in the EU in 2021. While this approach has a sound scientific basis, demand-based estimates are prone to underestimation due to misreporting and underreporting of prevalence and use, as self-reported data rarely reflect reality (Udrisard et al., 2022).

Obtaining information on the number of users and the amount of heroin they use is challenging. This is primarily because a large number of people who use heroin are dependent on the drug and may be living on the margins of society, and are thus unlikely to be included in surveys of the general population. Wastewater analysis, another source of information on drug use, cannot be performed for heroin because morphine, the most abundant metabolite of heroin, which can be used as a target residue to estimate heroin consumption, may also be an indicator of the commonly used medicines morphine and codeine. Many other potential indicators of heroin use have some time lag. For example, treatment indicators will detect opioid users only after approximately 13 years of use, and the number of opioid users entering treatment could be influenced by financial priorities and the availability and accessibility of services.

Based on previous research, a ratio of 3.5 to 1 between the total number of heroin users and known heroin users in treatment can be used to estimate problem drug use populations and thus to scale up demand-based estimates (Groom et al., 1998, as cited in Udrisard et al., 2022).

Further limitations include the lack of coverage of specific subgroups, such as prisoners, homeless people and other marginalised populations, in the current EU heroin market size estimate. This is due to a lack of data on the prevalence of drug use and the quantities used by these populations, which may be considerable. It would therefore be appropriate to consider these subpopulations specifically in demand-based estimates in the future (Udrisard et al., 2022).

A supply-side (top-down) approach

It is also possible to produce an estimate of the size of the heroin market using a top-down approach. There are two main models that can be used for this, namely a production-based approach and a seizure-based approach. The first involves assessing the amount of heroin available for consumption in a given country or region by taking global production estimates, subtracting the amount seized by law enforcement authorities or otherwise lost (spoiled, etc.) and then estimating the portion of the market share in that location. The amount available can then be multiplied by the local price (adjusted for purity, to account for adulteration) to arrive at the retail market value. There are several challenges with this approach, such as the accuracy of global production estimates and global seizure data, and how the national and EU market share can be assessed.

The seizure-based approach simply uses the amount of drug seizures and an estimated seizure rate to assess the quantities of drugs available on the market. However, no data are available that would allow an assessment of the seizure rate.

An alternative supply-side approach is based on estimates of the number of dealers and the average number of doses they sell (Rossi, 2013). Making such assessments may be possible. However, further studies are needed, initially at city level, to test this method and assess its suitability for use at national and EU level.

The EU opioid market is becoming increasingly complex

In Europe, the opioid market is becoming increasingly complex, incorporating new potent synthetic opioids, prescription opioid medicines and mixtures (see Section Synthetic opioid trafficking). While heroin remains by far the most common illicit opioid on the market at the EU level, this is not the case for all Member States. Ongoing monitoring and law enforcement action is needed to prevent further spread of synthetic opioids, some of which are relatively inexpensive and easy to manufacture (or to divert from legitimate sources).

While fentanyl and its derivatives, along with potent benzimidazole (nitazene) opioids, are still relatively niche in most places, they are increasingly available as part of the EU opioid market. Information on their use in Europe is limited, although existing evidence points to diverse national situations where there are signs of clusters of use limited to particular geographical locations. Historically, fentanyl and fentanyl derivatives have been the most common form of opioids used in Estonia. An increase in the availability of these substances was also observed in neighbouring markets, including Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden (see Section Synthetic opioid trafficking). An important caveat is that current monitoring systems may not accurately document trends in synthetic opioid use, and this is therefore an area that needs improvement.

Composite products, including heroin-fentanyl mixtures, have also been reported, as has the adulteration of illicit opioids with a range of potentially dangerous substances (see Box Adulteration of illicit opioids with xylazine and new benzodiazepines). The availability of these products represents a significant change in the risk environment for users of opioids and people who inject drugs, posing additional challenges for health responses.

While individual studies and monitoring data indicate that the misuse of prescription opioid medicines in the EU is limited, there is insufficient information to allow a more thorough assessment. For example, the diversion of methadone and buprenorphine from opioid agonist treatment is reported to be a significant problem in some countries (see Section Synthetic opioid trafficking).

There is also some evidence to suggest that the number of prescriptions for opioids used for pain management has been increasing. A published analysis of use and misuse of opioids in the Netherlands found an overall increase in opioid prescriptions by 80 % between 2008 and 2017 (from 4 109 to 7 489 prescriptions per 100 000 inhabitants). Oxycodone played a significant role, with a reported 350 % rise (from 574 to 2 568 prescriptions per 100 000 inhabitants) (Kalkman et al., 2019). The same study assessed several proxies for misuse and identified a similar increasing trend. The number of opioid-related hospital admissions tripled from 2.5 to 7.8 per 100 000 inhabitants, and between 2008 and 2015 the number of clients in treatment for opioid use disorders other than heroin increased from 3.1 to 5.6 per 100 000 inhabitants. Further, while opioid-related mortality remained stable between 2008 and 2014, at 0.21 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants, it increased to 0.65 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2017.

An increase in the use of prescription opioids affects the illicit market in a number of ways. For example, people who become dependent on opioid medications may turn to the illicit market to top up their medications or when their prescriptions expire. Also, an increase in the number of prescription opioids in circulation may provide new opportunities for diversion into the illicit market. Similar dynamics have been seen in the United States, where prescription opioids have fuelled the ongoing opioid epidemic.

In addition to the diversion of opioids from legitimate sources, falsified and counterfeit opioid medicines are available, raising issues of their own. Reports and public notices have emerged in a number of EU Member States in recent years, alerting users about new opioids mis-sold as fake medicines, such as oxycodone tablets containing nitazenes.

The EU is currently far from experiencing the opioid epidemic faced by the United States. While the EU’s healthcare systems – which are robust in terms of treatment and regulatory oversight – act as a protective factor, further preventive steps should be taken to address the threat posed by these developments.

Effects, risks and harms

Heroin is a central nervous system depressant. Like other opioids, it produces most of its effects by activating the mu (µ) opioid receptors in the central nervous system, which are involved in feelings of pain and pleasure and in controlling the heart rate, sleeping and breathing. The immediate effects of heroin use include a rush of euphoria, a warm flushing of the skin, dry mouth and a heavy feeling in the limbs. However, these effects are short-lived, and the drug quickly leads to a state of drowsiness, slowed breathing and clouded mental function. It can also cause nausea, vomiting and severe itching. The effects of heroin and their duration will differ based on several factors, including the amount taken and its purity and adulteration; the individual’s previous experience of using opioids, tolerance level and metabolism; and concurrent use of other drugs, including alcohol or medications.

The long-term effects of heroin use are numerous and can be severe. These include physical and psychological dependence, overdose and death. Chronic heroin use can cause a range of physical and mental health problems, including liver disease, kidney disease, collapsed veins, chronic pneumonia, and infections of the heart lining and valves. In addition to the physical and mental health effects of heroin use, there are also a number of social and economic harms associated with the drug. These include increased crime rates, lost productivity, healthcare costs, and strained family and community relations. In particular, the broader social costs associated with long-term dependence on heroin include higher rates of homelessness and criminality, particularly acquisitive crime.

Quantifying the harm

The use of heroin is associated with a disproportionate amount of acute and chronic harm, and this is compounded by factors that include the properties of the drug, the route of administration, individual vulnerability and the social context in which heroin is consumed. Although the number of people reporting use of heroin in the EU is low compared with drugs such as cannabis and cocaine, a large proportion of people who use heroin are dependent on the drug. This means that they use it more frequently and in larger amounts than is the case for other drugs.

Injecting – the main cause of health damage related to illicit heroin use

In Europe, heroin is predominantly sold in the base form as brown powder, while white powder (hydrochloride salt) and black tar are rare. While the availability of various preparations of heroin may influence the mode of use, the drug is most frequently smoked or injected. Heroin that is smoked is usually in the base form, which is appreciably more volatile than the salt (i.e. it vaporises more easily). For injecting use, citric acid solution is added to prepare heroin base as it is poorly soluble in water.

Injecting heroin is associated with many local and systemic complications, including increased risk of overdose, increased risk of infectious disease transmission (such as HIV and hepatitis C via needle sharing), vein damage, skin abscesses and infections.

Although heroin has historically been the main drug associated with injecting in Europe, this has been changing in recent years. Opioids are reported as the main injected drugs in 19 out of 24 countries for which data are available for clients entering treatment in 2021. Among first-time clients entering specialised drug treatment with heroin as their primary drug in 2021, or the most recent year available, 20 % reported injecting as their main route of administration (down from 38 % in 2013). However, levels of injecting vary between countries, from less than 10 % in Denmark, Spain, France and Portugal to 60 % or more in Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Slovakia.

Analysis of 1 845 used syringes by the ESCAPE network, covering 12 cities in 11 EU Member States between 2021 and 2022, detected 54 psychoactive substances. While these data are not nationally representative, they can be viewed as indicative of local-level drug use dynamics. In this sample of used syringes, heroin was the most commonly detected drug in five out of the 12 participating cities. Notably, injection of diverted opioid agonist medications, such as buprenorphine (Helsinki, Prague, Thessaloniki) and methadone (Dublin, Vilnius and Riga), was common in some cities (found in >30 % of syringes).

Carfentanil was commonly found in syringes in Vilnius, Lithuania (92 %) and Riga, Latvia (29 %). Another potent synthetic opioid, isotonitazene, was detected in 10 % and 26 % of syringes from Tallinn, Estonia, and Riga, respectively. In addition, xylazine, a potent veterinary tranquilliser, was detected in 13 % of syringes in Riga. Overall, a third of syringes contained residues of two or more drug categories, often including both opioid and stimulant drugs. This indicates frequent polydrug use or reuse of injecting equipment. Recognising the increasing complexity of injecting practices in Europe and the prominence of polydrug consumption in this context is therefore likely to have important implications for both understanding the harms associated with this mode of administration and the interventions designed to reduce such harms.

Overdose deaths related to heroin and other opioids

The most serious risk from overdose with opioids is rapid respiratory depression (slow and shallow breathing), which can lead to death. With heroin, this risk may be increased by a number of individual as well as contextual, especially social, factors, including the following:

- no or low existing tolerance to opioids;

- simultaneous use of other central nervous system depressants (such as other opioids, new benzodiazepines, alcohol and certain prescription medicines);

- using the substances while alone (typically in the home environment);

- lack of experience among dealers and users of dosing and effects, particularly of new synthetic opioids;

- changes in heroin market conditions, especially in cases of heroin adulteration or substitution with new synthetic opioids (Schneider et al., 2021; Strang, 2015).

Opioids, including heroin and its metabolites, often in combination with other substances, were estimated to be present in three quarters (74 %) of at least 6 166 fatal overdoses reported in the EU in 2021. While the data available have limitations in respect of quality and coverage, the information available suggests that opioids, usually in combination with other substances, remain the group of substances that are most commonly implicated in drug-related deaths. Overall, trends in deaths where opioids are implicated appear stable.

Significant shares of heroin-related overdose deaths were reported by Austria (67 % of overdose deaths), Italy (56 %) and Romania (43 %). In seven other European countries, heroin was found in approximately a quarter to a third of reported overdose deaths: Portugal (37 %), Denmark (36 %), Slovenia (33 %), France (33 % in 2020), Türkiye (32 %), Spain (28 % in 2020) and Norway (23 %). Meanwhile, in the north of Europe, less than one in six overdose deaths in Finland, Sweden and in the Baltic countries was reported to involve heroin in 2021. As such, while it remains the case that heroin is involved in a large proportion of opioid-related deaths, the data available increasingly suggest that other opioids are playing a more important role.

Available data suggest that polydrug toxicity is the norm and that opioids other than heroin, including methadone (and, to a much lesser extent, buprenorphine, with the exception of Finland and France), oxycodone and fentanyl, are associated with a substantial share of overdose deaths in some countries. In half of the 22 countries with post-mortem toxicological data available for 2021, at least one in five drug-induced deaths involved methadone. Buprenorphine was identified in 60 % of the drug-induced deaths reported in Finland in 2021, and 9 % of the deaths reported by the special register in France in 2020. In all other countries with available data, buprenorphine was reported in less than 5 % of fatal overdose cases, or not reported at all.

Tramadol was involved in less than 5 % (93) of reported overdose deaths in 12 European countries in 2021. In countries with available data, oxycodone was reported as being involved in 103 drug-induced deaths between 2020 and 2021, mainly in Denmark, Estonia, France and Finland (EMCDDA, 2023a).

While available data indicate that fentanyl and fentanyl derivatives were linked to 49 deaths in Europe in 2021, this excludes figures from Germany. With the inclusion of data from Germany, this number appears to be much higher, rising to a minimum estimate of 137 deaths. Preliminary analysis, however, suggests that many of these fatalities might be associated with diverted fentanyl medicines rather than illicit fentanyl.

Potent synthetic opioids, such as the fentanyl derivative carfentanil and benzimidazole (nitazene) opioids, consumed in the context of polydrug use, do not currently feature prominently in the data available at EU level but are observed to be causing an increasing number of deaths in the Baltic countries, including in Estonia and Lithuania in 2021. Preliminary data indicate that in 2022, Estonia experienced an increase in drug overdose deaths involving isotonitazene, metonitazene and protonitazene. In Latvia, both the national statistics and the forensic registers have reported a three-fold increase in the number of drug-induced deaths in 2022 compared with 2021. Part of this reported increase relates to improved laboratory capacity in 2022. As such, the increase should be interpreted cautiously, although recent shifts in the opioid market are also likely to have played a role. Nitazenes appeared to be involved in a number of fatalities in 2022 and xylazine was identified in one case. Preliminary first-quarter data for 2023 from Latvia also suggest that benzimidazole opioids were involved in a number of drug-related deaths.

The adulteration of heroin with fentanyl and isotonitazene, leading to fatal overdoses among users, has been reported to Europol by UK authorities since mid-2021. The UK Home Office is aiming to tighten controls on two other synthetic opioids, namely brorphine and metonitazene. Brorphine, known as ‘purple heroin’, has been detected in fake pain medication tablets, such as oxycodone, and in the blood samples of at least 60 fatal and non-fatal overdoses involving users of multiple substances (Home Office, 2022).

Acute heroin toxicity: Euro-DEN Plus data

Heroin remained the third most commonly reported drug in acute drug toxicity presentations in Euro-DEN Plus hospitals in 2021, accounting for 15 % of all reported cases. Opioids were found in 20 of the 24 European hospitals participating in 2021. Of these, half of the hospitals reported that 6 % or more of their presentations involved heroin. A fifth to a quarter of the presentations involved heroin in one hospital in Oslo (Norway), in Drogheda and Dublin (Ireland), in Ljubljana (Slovenia) and in Msida (Malta). In contrast, small proportions of the presentations involved heroin in the hospitals in Belgium, the Netherlands, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and in the centres in Paris (France) and Barcelona (Spain). Most presentations with heroin were among middle-aged men, and in 12 of the 20 centres no cases were aged less than 25 years. In half of the centres, women represented 11 % or less of the presentations with heroin.

Heroin use and pregnancy

The use of heroin and other opioids during pregnancy has been linked to a number of neonatal complications, including opioid withdrawal, postnatal growth deficiency, neurobehavioural problems and a 74-fold increase in sudden infant death syndrome (Minozzi et al., 2008; Patrick et al., 2020). Repeated use of heroin and withdrawal symptoms are associated with increased neonatal mortality (Jansson et al., 2009). High rates of intrauterine growth retardation have also been reported in heroin-dependent mothers (Binder and Vavrinkova, 2008), in addition to elevated risk of low-birthweight infants from maternal heroin use compared to those from non-drug-using mothers, and prematurity and small-for-gestational-age babies (Bell and Harvey-Dodds, 2008; Madgula et al., 2011; Yazdy et al., 2015).

Among pregnant women who continue illicit intravenous heroin consumption, the risks of medical complications such as infectious diseases, endocarditis, abscesses and sexually transmitted diseases are also increased (Winklbaur et al., 2008).

Heroin use and crime

There is a well-established, albeit complex, relationship between illicit opioid use and crime. Although high-risk opioid users are much more prevalent in the criminal justice system than in the general population, the relationship between opioid use and crime differs between individuals, and for the same individual over time.

There is strong evidence that problem heroin use can amplify offending behaviour, particularly related to economic-compulsive crime, whereby users of heroin or other opioids engage in economically oriented crime to support a compulsive pattern of use (Goldstein, 1985). A meta-analysis of studies on the relationship between drugs and crime concluded that the likelihood of committing crimes that were not drug possession offences is up to eight times greater for people who use drugs than for those who do not (Bennett et al., 2008).

Few opioid users resort to violence to acquire money for drugs, though some may engage in violent crime, such as assault, homicide or robbery. However, the extent to which opioid dependence is associated with these more serious forms of crime is less apparent (White and Gorman, 2000). There is limited research examining the prevalence of drugs other than alcohol in penetrating injuries (such as gunshots, explosive devices and stab wounds), and most of the published research originates from the United States (Lau et al., 2023).

Although heroin-using offenders have high rates of offending, they also have high rates of a range of other problems, such as homelessness, unemployment, low educational attainment and disrupted family backgrounds, making the relationship between drugs and crime more complex. The association between opioid use and crime highlights the importance of addressing use as a means of reducing criminal behaviour and improving public safety. Treatment for opioid-dependent individuals can help to reduce the demand for illicit drugs and decrease associated crime.

Heroin can also be associated with an increased risk of being a victim of violence, due to altered perceptions and impaired judgement (Gilbert et al., 2012). The risk of being subject to violence may also be linked to the perpetrator’s perception that the victim’s substance use can be used to justify their violent behaviour (Gilbert et al., 2001). It is important to note that the risk of experiencing heroin-related violence is likely to be influenced by a range of situational factors, such as setting, socioeconomic status, other drug use, and a history of mental illness and trauma.

Women involved in the sex trade have been identified as a sub-group who are particularly at risk of experiencing gender-based violence in the context of drug use, through engagement in the sex trade or in their intimate relationships (EMCDDA, 2023b). Participation in the sex trade is often intertwined with drug use; for example, in some countries, it is estimated that between 20 % and 50 % of women who inject drugs are involved in the sex trade. Many women who trade sex for drugs have limited power to practise safe sex or follow safe injecting practices and are at risk of experiencing violence and imprisonment. These women also face a greater degree of stigma, through both their drug use and their involvement in the sex trade (EMCDDA, 2023b).

Treatment and harm reduction interventions

The available evidence strongly supports enrolment in opioid agonist treatment as a protective factor against opioid overdose and some other causes of death, with positive outcomes also found with regard to the use of illicit opioids and other drugs, reported risk behaviours, offending and drug-related harms (EMCDDA, 2021d, 2023a; Mayet et al., 2005; Strang et al., 2012, 2020).

In the EU, opioid users represent the largest group undergoing specialised drug treatment, mainly in the form of opioid agonist treatment, typically combined with psychosocial interventions (EMCDDA, 2023a). Overall, opioid agonist treatment was received by about half of all high-risk opioid users in the EU in 2021, an estimated 511 000 individuals. However, there are differences between countries. Trends from countries that consistently report data on clients receiving opioid agonist treatment between 2010 and 2021 show an overall stable trend of treatment levels during this period, with little fluctuation in the number of clients. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, EU Member States sought to ensure continued access to opioid agonist treatment for people engaged in high-risk drug use. A comparison of treatment data between 2019 and 2021 indicates that the number of clients remained stable, with only Croatia, Cyprus and Slovakia reporting a decrease greater than 10 % of clients during this period. Some countries have continued to expand treatment coverage, with 10 countries reporting increases in the numbers receiving agonist treatment between 2015 and 2021, including Romania (+40 %), Poland (+37 %) and Sweden (+23 %).

EMCDDA data on treatment and harm reduction services available in prisons in 2021 show that continuity of opioid agonist treatment was available in all EU Member States apart from Slovakia, as well as in Norway and Türkiye. Needle and syringe exchange was available in prisons in three EU Member States (Germany, Spain and Luxembourg) (1) and take-home naloxone was available in such settings in a further three EU Member States (France, Estonia, Germany) and Norway (EMCDDA, 2022b).

The data available on the characteristics of those receiving opioid agonist treatment underline the long-term nature of opioid problems and that Europe’s cohort of heroin users is ageing. This is illustrated by the fact that over 75 % of clients in opioid agonist treatment are now aged 40 or older, while less than 10 % are under 30 years old. This has important implications for service delivery, with services having to address a more complex set of healthcare needs in a population that is becoming more vulnerable due to other age-related health and social issues.

Alongside opioid agonist treatment, needle and syringe exchange programmes and other harm reduction interventions were in place in all EU Member States and Norway in 2022. However, coverage and access to these programmes remains a challenge, with only five of the 17 EU countries with available data reaching the World Health Organization service provision targets in 2021.

Currently, 15 countries report the provision of take-home naloxone to prevent overdose deaths and 10 countries report having at least one supervised drug consumption room. Naloxone works as a safe and effective antidote to reverse the respiratory depression caused by opioids (Boyer, 2012; Britch and Walsh, 2022; Strang et al., 2019). However, coverage of these interventions remains uneven within and across countries in the EU. In addition, 12 countries have some type of drug checking service, which can help prevent harms by allowing users to find out what substances are present in the drug they have acquired and intend to consume.

Distribution of heroin and other opioids

Most of the people who use heroin and other opioids buy their drugs offline on ‘street’ markets. However, as with other drugs, opioids are also distributed across the EU via a range of digital channels, including darknet markets. The quantities offered online are typically small, and purchases are usually delivered using post and parcel services (see Section Fluidity of routes, methods of transportation and modi operandi). In addition to parcel delivery, user-level distribution takes place by means of personal handover or by agreeing on a location where the drugs are left for pick-up.

Although online retail distribution of heroin appears to remain marginal compared with other supply methods, it is important to understand its scope. A total of 2 003 listings (sale offers) of opioids (excluding new opioids) were identified based on 2021 data from eight major darknet markets, namely Versus (647), World (636), Dark0de Reborn (397), ASAP (112), Hermes (71), Alphabay-v3 (66), Cypher (51) and Royal (23); these were reported as being shipped from an EU country. To put this in context, although not directly comparable, a similar scanning exercise conducted in 2021 found 13 269 listings for cannabis and 6 750 for amphetamine products (For more information on the data source, see Section Overview of data and methods).

The available data suggest that most of the opioid listings in 2021 originated from the Netherlands (48 %) and Germany (32 %). Other reported EU origin countries included France (10 %), ‘Europe’ (5 %), Poland (2 %) and Belgium (1 %). A further 3 % of opioid listings identified a range of other EU countries as shipping origin (see Figure Proportion of opioid listings on major darknet markets by EU Member State, 2021).

Notes: * ‘Other’ comprises Austria, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain.The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Overall, heroin was the main opioid identified in 70 % of the listings (1 407 out of 2 003). Around 60 % of these listings offered shipping from the Netherlands, just under 30 % from Germany and around 6 % from France. Caution is needed in interpreting these data, as neither the number of individual sellers offering heroin on these marketplaces nor the number of transactions can be extrapolated from the number of listings alone. Nonetheless, the number of listings has been used as a valid indicator of the scope of activity on darknet markets.

There also appears to be a growing online market for opioids other than heroin, mainly synthetic opioids such as methadone-, codeine- or oxycodone-containing tablets, identified in 30 % of the opioid market listings (596 out of 2 003) in 2021. However, these findings should be viewed with caution due to an absence of forensic testing and evidence on the actual substances sold in these listings.

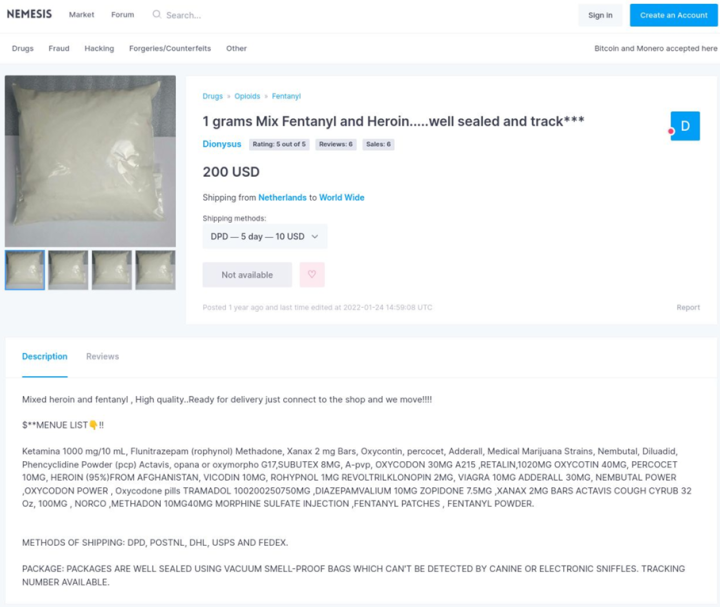

In addition, heroin-fentanyl combinations appear to be available on darknet markets. An example of this can be found in a listing reportedly shipping from the Netherlands (see Screenshot Fentanyl-heroin mixture listed on a darknet market, shipping from the Netherlands). The availability of such products represents a significant change in the risk environment for people who inject drugs.

New benzimidazole (nitazene) opioids, including isotonitazene, etazene, etomethazene, metonitazene and protonitazene, also appear to be available on darknet drug markets. Listings for these substances have been associated with several EU Member States (Czechia, France, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Sweden), which were noted as shipping origins on major darknet markets in 2022.

Of particular concern is the online marketing of new opioids mis-sold as falsified (fake) medicines. In recent years, reports and public notices have been issued in a number of EU Member States to alert people about new opioids mis-sold as fake medicines, such as oxycodone tablets containing new opioids. For example, in November 2021, Slovenia reported a falsified ‘Percocet’ tablet, reportedly purchased on a darknet market, that was found to contain etonitazepine (DrogArt Association, 2021).

The criminal use of the online environment to trade synthetic opioids, or medicines containing or adulterated with such compounds, could further increase in the EU as criminals act upon new opportunities, such as an increased demand for these products (see Box Operation Earphones disrupts the trafficking of fentanyl into Italy).

In addition to falsified medicines, there is also an online market for opioid medicines diverted from legitimate pharmacy supplies and sold on the surface web (see Box Poland-based online market supplying illegally diverted opioid medicines to the United States and the United Kingdom).

(1) In Spain, needle and syringe programmes are implemented under central jurisdiction in all Spanish prisons where there are people injecting drugs, while in Luxembourg, the two prisons functioning in the country have implemented them. In Germany, a single programme exists in a women’s prison in Berlin (EMCDDA, 2022b).

Source data

| Country | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|

| Netherlands | 48 |

| Germany | 32 |

| France | 10 |

| Europe | 5 |

| Poland | 2 |

| Belgium | 1 |

| Other* | 3 |

References

Consult the list of references used in this module.