Prisons and drugs: health and social responses

Introduction

This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and social responses to drug problems: a European guide. It provides an overview of what to consider when planning or delivering health and social responses to drug-related problems in prisons, and reviews the available interventions and their effectiveness. It also considers implications for policy and practice.

Last update: 6 July 2023.

Contents:

Overview

Key issues

People who commit criminal offences and enter the criminal justice system have higher rates of drug use and injecting than the general population. They are also often repeat offenders and make up a significant proportion of the prison population.

Drug use can be linked to offending in a number of ways: some offenders with drug problems are incarcerated for use or possession offences; many others are imprisoned for other drug law offences or crimes, such as theft committed to obtain money for drugs. The complex healthcare needs of these individuals should be assessed on entry to prison with regular follow-ups thereafter.

Drug use also occurs in prisons and presents a public health and safety risk to both inmates and prison officers. The risk of overdose death for people who use opioids is particularly high in the period immediately after release from prison, making continuity of care an important focus.

People who use drugs and come into contact with the criminal justice system are a dynamic population that has regular contacts with the community. In responding to drug-related problems in prison settings, the health of people both in prison and in the community can be improved, producing an overall societal benefit.

The international drug conventions recognise that people with drug dependence problems need health and social support and allow for alternatives to coercive sanctions to help them address their drug-use problems.

Evidence and responses

In general, interventions that are effective in tackling drug problems in the community are also found to be effective in prisons, although there tend to be fewer studies to support this. In particular, the availability of opioid agonist treatment for people with opioid dependence is recommended.

Two important principles for health interventions in prison are equivalence of care to that provided in the community and continuity of care between the community and prison on admission and after release. This implies that all appropriate prevention, harm reduction and treatment services should be available within prisons, and also that particular attention should be paid to service provision around admission and release.

Encouraging drug-using offenders to engage with treatment can offer an appropriate alternative to imprisonment, with this approach having a number of potential positive effects, such as reducing drug-related harms for individuals, preventing the damaging effects of detention and contributing to reducing the costs of the prison system. More and better evaluations of the different models of interventions are needed.

European picture

- Many interventions that have been shown to be effective in the community to reduce drug demand and to prevent and control infectious diseases have been implemented in prisons in Europe, but often following some delay and with insufficient coverage.

- Although opioid agonist treatment in prisons is reported by all but one country monitored by the EMCDDA, it remains available to only a small proportion of the people who need it.

- The provision of clean injecting equipment is available in only a few prisons in Europe.

- Many European countries have partnerships between prison health services and providers in the community to ensure continuity of care on prison entry and release.

- Preparation for prison release, including social reintegration and prevention of overdose among opioid injectors, is reported by most countries, but few include the provision of naloxone upon release.

- Alternatives to prison are available in many countries in Europe, although approaches to diversion vary considerably and, overall, availability and implementation remain limited.

Key issues related to prison and drugs

People who commit criminal offences and enter the criminal justice system and prisons report higher lifetime rates of drug use and more harmful patterns of use (including injecting) than the general population. This makes prisons and the criminal justice system an important setting for drug-related interventions.

Drug use can be linked to offending in a number of ways: use or possession may constitute offences against the drug laws; crimes may be committed in order to obtain drugs or fund their purchase; offences may be committed under the influence of drugs; and there are also crimes that are linked to the drug trade, such as violence between different groups of drug suppliers.

The majority of recorded drug law offences in most EU countries relate to cannabis use or possession. Acquisitive crimes, such as robbery, theft and burglary committed to fund drug use, are more often reported among people who have problematic patterns of use. This latter group are often repeat offenders and can make up a significant proportion of the prison population.

The international drug conventions recognise that people with drug dependence problems need health and social support and allow for alternatives to coercive sanctions to help them address their drug use problems. Nevertheless, many people with problematic drug use are still incarcerated.

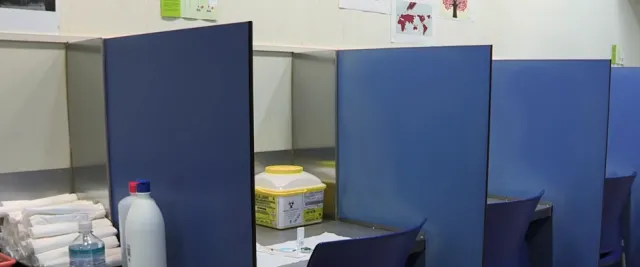

Drug use that occurs in prisons may present a public health and safety risk to people in prison and prison officers. People in prison who use drugs can exhibit complex healthcare needs that have implications for the responses offered at intake, during incarceration and on release (see Figure 'Drug-related and other health and social care interventions targeting people who use drugs in prison, by phase of imprisonment'). As the average duration of a prison sentence for this group is a few months, they remain a dynamic population that has regular contact with the community — a situation that has public health implications. In responding to drug-related problems in prison settings, the health of both the people in prison and the community they return to can be improved, producing an overall societal benefit.

A particular issue of concern in some countries is the increasing use of synthetic cannabinoids in prisons. This may be due to these substances being generally undetectable by the random drug tests used in prisons in some jurisdictions, or to their being cheaper than other drugs and easier to smuggle into prison (see Spotlight on synthetic cannabinoids).

Evidence and responses to drug-related issues in prison

Responses in prisons

Many drug-related interventions that have been demonstrated to be effective in the community have been implemented in prisons in Europe.

Two important principles for health interventions in prison are equivalence of provision to that available in the community and continuity of care before and after release from prison. Human rights principles should also be respected: inmates should be accorded humane treatment and access to care, while patient consent and confidentiality should be respected, with humanitarian assistance made available for the most vulnerable individuals. The clinical independence of health staff in prison is also important to ensure access to treatment.

The equivalence of care principle obliges prison health services to provide people in prison with care of a quality equivalent to that available to the general public in the same country, including drug treatment and harm reduction interventions. Barriers, whether legal or structural, should be overcome to guarantee high-quality treatment and care for people in prison.

Continuity of care between services in the community and prison should be ensured both on entry to prison and on release. This principle should also apply to drug treatment, including opioid agonist treatment (OAT) and all types of healthcare.

Interventions at prison entry

To meet these basic requirements in relation to the continuity and quality of care, prison reception routines need to include systems for identifying individuals with high treatment needs immediately on arrival. Health assessment on entry to prison is a core practice in prison healthcare regimes. The aim is to diagnose any physical or mental illnesses, provide the required treatment and ensure the continuation of community medical care. In addition, a proper needs assessment and review must be undertaken to ensure that treatment is matched to each individual’s needs. Where detoxification is appropriate this should be properly managed. Acute detoxification management may include symptomatic treatment of the effects of withdrawal, and may benefit from the use of clinical tools to monitor symptoms. The medical consultation upon entry to prison is also an opportunity to give the individual information about treatment and prevention, raise their awareness of risk and distribute harm reduction materials.

Interventions during the prison stay

Drug treatment programmes in prison can be carried out in a number of ways. Outpatient treatment may be conducted in medical clinics or common spaces inside prison facilities, and may include psychosocial interventions, pharmacological treatment and training activities.

Residential treatment inside prison is provided in special units or wings to which people with drug-related problems are assigned after a needs assessment. Therapeutic communities are the main form of residential treatment in prison and they operate in a similar manner to residential programmes in the community. Evidence of effectiveness is limited but suggests that therapeutic communities in prison settings may be beneficial in reducing drug use, re-arrest rates and re-incarceration among drug offenders. Also available in prison are drug-free units — specific residential wings that although not necessarily focused on drug treatment, seek to provide a drug-free environment inside prison to support people in remaining abstinent. However, evidence of their effectiveness is lacking.

Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial interventions include a range of structured therapeutic processes that address both the psychological and social aspects of a client’s behaviour, and vary in duration and intensity. Three general types of psychosocial intervention have been used to treat people who use drugs: contingency management; cognitive behavioural therapy; and motivational interviewing. These techniques are often used in conjunction with pharmacological interventions. While some evidence exists for the effectiveness of their use in the community, more studies are required in the prison setting.

Opioid agonist treatment

In Europe, OAT in the form of methadone or buprenorphine is the main treatment provided in the community for opioid dependence. In prisons where OAT is available, those who have been receiving it in the community can continue to be treated in prison. OAT may also be initiated in prison, or re-initiated before the end of a sentence. There is evidence to suggest that providing OAT with methadone during incarceration reduces injecting risks and increases engagement with community treatment after release from prison. Continuity of care when entering and leaving prison is a critical issue for those undergoing OAT because there is a high risk of overdose and or transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection when treatment is disrupted. Current evidence supports the provision of OAT in prison, particularly if continued in the community, to reduce mortality after prison release.

Used to prevent relapse in opioid-dependent individuals, extended-release naltrexone is a sustained-release monthly injectable formulation of the full mu-opioid receptor antagonist, however, much uncertainty remains around its effectiveness and more research on this topic is warranted.

Peer interventions

Peer interventions, delivered to people in prison by current or former people in prison, aim to improve individuals’ health and reduce risk factors. Different modes of peer-to-peer activities have been identified, including education, support, mentoring and bridging roles. While some studies suggest that these interventions may be effective in reducing risk behaviour, particularly with regard to the use of new psychoactive substances, there is as yet no strong evidence supporting this. Partnerships between prison health services and providers in the community have also been important in delivering health education and treatment interventions for new psychoactive substance use and related harm in prisons.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction interventions are implemented in prison to reduce the health and social harms of drug use to the individuals and the prison community. In particular, prisons can be a core setting for engaging with people who inject drugs and who may have been hard to reach in the community, allowing the provision of harm reduction, counselling, testing and treatment services before they return to the community.

A range of measures are recommended to reduce harms related to drug use. These include OAT (see above), testing and treatment for infectious diseases, vaccination, the distribution of sterile injecting equipment, and health promotion interventions focused on safer injecting behaviour and reduced sexual risk behaviour. Providing universal voluntary testing programmes for a range of infections (blood-borne viruses, sexually transmitted infections and tuberculosis) on entry to prison and upon release, alongside rapid treatment where necessary, can reduce the spread of infectious diseases within the prison setting as well as in the wider community (see Drug-related infectious diseases: health and social responses). Training prison healthcare staff about communicable diseases and the promotion of testing may increase active case finding and the implementation of these programmes. UN/WHO guidance recommends the provision of harm reduction measures in prison, including needle and syringe programmes, but such practices are currently rare — scaling up these programmes could make an important contribution to health improvement.

Interventions upon release from prison

Specific pre-release measures are needed for those who use or have used drugs, as people leaving prison have particular health-related vulnerabilities, including the risk of relapse into drug use, overdose and overdose death, and the transmission of infectious diseases. To ensure an easier transition into community treatment, cooperation between services operating inside the prison and health and social services outside in the community is especially important. There are two key interlinked components in interventions for release from prison: connections to services in the community in order to ensure that ongoing treatment for substance use disorder and infectious diseases continues; and prevention of overdose deaths in the period immediately following release from prison.

The risk of overdose death for people who use opioids is particularly high shortly after release from prison. The main responses aiming to reduce opioid-related deaths, both in the community and in prison, involve a set of interventions geared towards preventing overdoses from occurring in the first place and a set focusing on preventing death when overdoses do occur. A number of interventions are implemented with a view to reducing the danger of overdosing, including pre-release counselling, training in first aid and overdose management, optimising referral to ensure continuity of drug treatment between prison and community, and distributing naloxone. Naloxone is an opioid antagonist medication used to reverse opioid overdose. In recent years, there has been an expansion of take-home naloxone programmes that provide overdose training and make the medication available to those likely to witness an opioid overdose. While it is accepted that naloxone can reverse the potentially fatal effects of an opioid overdose, more data are needed to confirm the impact of take-home naloxone programmes on mortality.

Drug-related problems are just one of many vulnerabilities experienced by people who spend some part of their lives in prison. Social marginalisation and inequality are significant risk factors for both drug use and offending behaviour, requiring integrated multi-agency approaches that address substance use and drug-related problems along with other important health and social problems.

Alternatives to coercive sanctions

Alternatives to coercive sanctions are recognised as having the potential to reduce drug-related harms by diverting offenders with drug problems into programmes that may help them tackle their substance misuse issues, which often underpin their offending. Diverting offenders with problem drug use towards rehabilitative measures and away from incarceration can have a number of positive effects, such as preventing the damaging effects of detention and contributing to reducing the costs of the prison system (e.g. infrastructure, staff, etc.). However, few programmes have been evaluated to date and therefore the evidence base is limited. Where there have been evaluations, these have mostly been undertaken outside Europe with generally weak designs.

There are many different types of alternatives to coercive sanctions, and these may be applied at different stages of the criminal justice process, from arrest to sentencing. A recent European study found 13 different forms of alternatives to coercive sanctions available in the 27 EU Member States. These ranged from a simple caution, warning or no action, to referral to specialised drug treatment. Alternatives to prison are a specific type of alternative to coercive sanctions and include receiving a suspended sentence conditional on attending drug treatment or agreeing to undergo treatment in prison to shorten the incarceration period.

Although the evidence is not strong, the key to success seems to be having a range of interventions available that are appropriate to the needs of individuals with different types and levels of drug problems. Studies are needed to improve the evidence base around alternatives to coercive sanctions, with a particular focus on the groups that can benefit most from them and the stages of the criminal justice process at which they are best applied.

Overview of the evidence on … interventions in prison and the criminal justice system

| Statement | Evidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Effect | Quality | |

| Methadone received during incarceration reduces injecting risks and increases community treatment engagement after prison release. | Beneficial | Moderate |

| Providing OAT, particularly if OAT is continued in the community, reduces mortality after prison release. | Beneficial | Moderate |

| Therapeutic communities in prison may reduce drug use, arrest rates and re-incarceration among drug offenders. | Beneficial | Low |

Evidence effect key:

Beneficial: Evidence of benefit in the intended direction. Unclear: It is not clear whether the intervention produces the intended benefit. Potential harm: Evidence of potential harm, or evidence that the intervention has the opposite effect to that intended (e.g. increasing rather than decreasing drug use).

Evidence quality key:

High: We can have a high level of confidence in the evidence available. Moderate: We have reasonable confidence in the evidence available. Low: We have limited confidence in the evidence available. Very low: The evidence available is currently insufficient and therefore considerable uncertainty exists as to whether the intervention will produce the intended outcome.

European picture: availability of drug-related interventions in prison

Several measures have been discussed and implemented in European countries that could potentially affect imprisonment rates, reducing the number of people serving prison sentences or undergoing other forms of punishment for drug use and drug-related offences. These include decriminalising drug use, abolishing short-term sentences of less than 12 months and providing alternatives to coercive sanctions.

Alternatives to prison are available in many countries in Europe, although approaches to diversion vary considerably and overall availability remains limited. Few countries in Europe have chosen to adopt widespread rehabilitative approaches. Where such policies are adopted, they are often implemented without robust monitoring or evaluation, although investment in such initiatives could show dividends in the long run by providing information that can be used to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of these programmes.

Interagency partnerships between prison health services and providers in the community exist in many countries in order to ensure the delivery of health education and treatment in prison and continuity of care upon prison entry and release.

Compared with the early 2000s, the availability and levels of provision of health and social care services targeting the needs of people who use drugs in prison have improved in several European countries; yet, for the most part, these individuals are faced with a limited range of treatment options, and the principles of equivalence and continuity of care remain unachieved in the majority of countries in Europe.

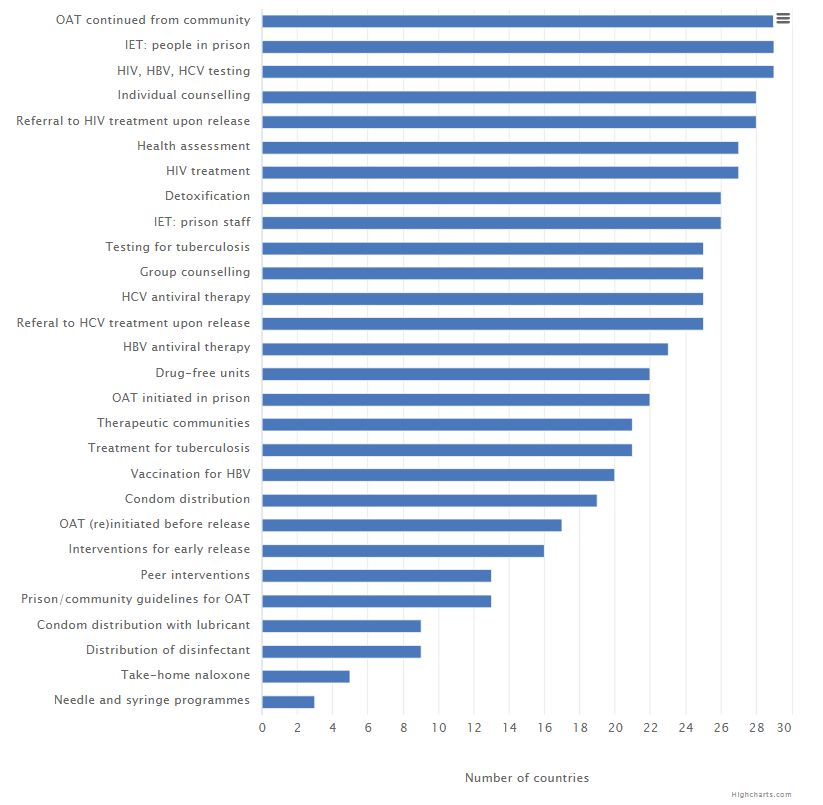

Many drug demand reduction interventions that have been shown to be effective in the community have been implemented in prisons in Europe, although often following some delay and with insufficient coverage (see Figure 'Number of countries reporting availability of interventions targeting people who use drugs in prison in Europe, 2019'). Opioid agonist treatment in prison, for instance, while implemented in all reporting countries but one, remains available to only a small proportion of the people who need it.

Approaches, target groups, and modalities of harm reduction measures in prison vary by country. Interventions to prevent and control infectious diseases, including testing and hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination and the treatment of HIV and hepatitis C, as well as the provision of education on infection risk and prevention, are available in prisons in most reporting countries. However, in practice, access to testing and treatment remains low. The provision of clean injecting equipment is rare and available in only a few prisons in Europe.

Many European countries report a lack of appropriate responses to the use of new psychoactive substances in prisons. In some instances, information initiatives and training focusing on these substances are provided to prison staff. Available responses elsewhere in the world also remain limited but include a comprehensive programme implemented in the United Kingdom to counteract new psychoactive substances, which had provisions for associated legislative changes; a national strategy and action plan; a smoking ban; the development of new drug tests; information campaigns; and included a toolkit to support prison staff in addressing the use of such drugs.

Most countries in Europe report drug testing in prisons. However, the extent to which drug testing is used, and the occasions and circumstances that trigger it vary across jurisdictions, and data are generally scarce. For example, Finland typically reports thousands of drug tests performed per year, while in Luxembourg drug testing is triggered only by a suspicion of use, and even then it is rarely applied.

Most countries carry out some kind of preparation for prison release, including social reintegration and referral to external services. Programmes to reduce the high risk of drug overdose death among opioid injectors in the period after leaving prison are reported in a number of countries. These initiatives include training and information provision on overdose risk reduction and, in a few cases, supplying individuals with naloxone upon release from prison.

Implications for policy and practice

Basics

-

The principles of equivalence of care and continuity of care require the provision of the same range of evidence-based interventions for people with drug problems in prison as are available in the community, alongside mechanisms to ensure continuity of treatment. This is especially important for those incarcerated for short periods.

-

Many drug-related interventions that have been shown to be effective in the community have been implemented in prisons across Europe, yet people in prison are still faced with a limited range of treatment options.

-

It is important that preparation for prison release includes activities to support social reintegration and training on overdose prevention — the provision of take-home naloxone should also be considered.

-

Alternatives to coercive sanctions are recognised in the international conventions as a potentially valuable option for offenders with drug problems.

Opportunities

-

Prison provides a setting where interventions may reach particular groups of people who use drugs who are often hard to reach by drug and health services in the community.

-

In providing harm reduction, counselling, testing and treatment services to people in prison before they return to the community, the health of both those in prison and the community to which they return can be improved, producing an overall societal benefit.

-

Increasing the use of alternatives to coercive sanctions through a review of the regulations that govern their application and addressing public and professional attitudes to their use may have the potential for improving long-term outcomes and reducing criminal justice expenditure.

Gaps

-

While most European countries report the provision of opioid agonist treatment in prisons, the availability and coverage of such services for people who use opioids remains low in many countries — scaling up these programmes could make an important contribution to health improvement.

-

Studies are needed to improve the evidence base around alternatives to coercive sanctions, with a particular focus on the groups that can benefit the most from them and the stages of the criminal justice process at which they are best applied.

-

Data on the prevalence of drug use among people in prison, the need for addiction services and the availability of such interventions in prison remain scarce. A better understanding of these issues is required to inform policy decisions, needs assessments, service planning and the organisation of treatment in prison.

Data and graphics

Note: This figure presents a simplified categorisation of the drug-related interventions that may be provided in prison. Different phases may overlap, and settings and modalities for the provision of drug treatment may also differ between countries and prisons.

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT). Information Education Training (IET). See the source table for this grpahic.

Further resources

EMCDDA

- Prison and drugs in Europe: current and future challenges, 2021.

- Impact of COVID-19 on drug markets, use, harms and drug services in the community and prisons, 2021.

- European Questionnaire on Drug Use among People living in Prison (EQDP), 2021.

- Public health guidance on prevention and control of blood-borne viruses in prison settings, 2018.

- Systematic review on the prevention and control of blood-borne viruses in prison settings, 2018.

- New psychoactive substances in prison, 2018.

- Public health guidance on active case finding of communicable diseases in prison settings, 2018.

- Alternatives to punishment for drug-using offenders, EMCDDA Papers, 2015.

Other sources

- WHO. Status report on prison health in the WHO European Region, 2019.

- ECDC. Systematic review on the diagnosis, treatment, care and prevention of tuberculosis in prison settings, 2017.

- European Commission. Study on alternatives to coercive sanctions as response to drug law offences and drug-related crimes, 2016.

- WHO. Prisons and health, 2014.

About this miniguide

This miniguide provides an overview of what to consider when planning or delivering health and social responses to drug-related problems in prisons, and reviews the available interventions and their effectiveness. It also considers implications for policy and practice. This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and Social Responses to Drug Problems: A European guide.

Recommended citation: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2022), Prisons and drugs: health and social responses, https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/mini-guides/prisons-and-drugs….

Identifiers

HTML: TD-07-22-093-EN-Q

ISBN: 978-92-9497-723-6

DOI: 10.2810/880339