A conversation with EMCDDA Director Alexis Goosdeel (February 2022)

Doing the right thing to tackle Europe's drugs problem

A conversation with EMCDDA Director Alexis Goosdeel

(Feature article No 1/2022)

(January 2022) EMCDDA Director Alexis Goosdeel talks about the complexities of Europe's drugs problem today and how the agency is adapting to address new challenges...

The changing face of Europe's drugs problem

Use of illicit drugs has changed beyond all recognition since the agency began working in this field over 25 years ago. Now considerably more complex, the drug phenomenon covers a much broader range of substances, behaviours and people. Overall, the situation is highly worrying and unlikely to change fundamentally in the next few years.

Drugs are Everywhere. Established drugs have never been so accessible, or available in such large quantities, and potent new substances continue to emerge.

Today, almost Everything can be a drug, as the lines blur between licit and illicit substances and between synthetic and plant-based drugs.

Everyone can be affected, whether directly or indirectly. Users may have addictive or behavioural problems. Non-users may know, or be affected by, someone struggling with these issues. The sheer increase in the drugs available on the market impacts on the whole community.

This wider picture can be summed up in three words: Everywhere, Everything, Everyone.

This broad framework guides our work as we analyse and explain the changes in the dimensions and characteristics of the drugs problem today. We provide evidence-based analysis to inform decision-makers and to help those working in the field identify the appropriate responses.

Importance of data

The EMCDDA was set up in 1993 with one mission: to be an information provider. Solid national data were sketchy or non-existent at that time, preventing the emergence of a reliable overall European picture. Policymakers looking to prepare suitable responses, particularly to the then ongoing heroin injecting epidemic, needed to understand the scale, causes and impact of the problem.

Responding to the challenge, the agency developed the methodologies and networks to collect key data sets; it then collated, analysed and disseminated the findings. We were, and continue to be, highly successful in implementing this original mission.

Inevitably, many things have changed over almost three decades. The agency has responded accordingly and continues to learn from experience. Data are a case in point.

Over time, the agency received increasingly large quantities of new data every year from multiple sources. Member States relied on us to publish the data as we were the central source of reliable information on drugs.

We broke new ground with innovative monitoring methods. Each new piece of evidence brought the overall picture into clearer focus. This meant that, every year, we could pinpoint something new, which improved our understanding of the drugs problem. Piece by piece, we were able to add to a complex jigsaw puzzle.

In the past, we received and analysed data and wrote comprehensive reports. But now, we are aiming to be more proactive with our data. What are the main priorities of decision-makers and key professionals and why do they need the data? Do they want to know about crack cocaine availability and use, drug consumption rooms or cannabis policies? Our reports and briefings will now focus on the answers to the questions being asked.

Our investigations enable us to highlight specific issues, such as the prevalence of crack cocaine use in some major cities, or national debates on whether to legalise cannabis. We can also highlight new information, developments and responses to ongoing problems.

But this short-term focus cannot disguise the fact that long-term drug trends do not change quickly. What is happening now has been happening for a while and will continue to do so. To fully understand the problems we face, and appreciate the significance of new information, we cannot simply ask a binary question: is the situation better or worse than last year? The picture is more complex.

Changing drug-use patterns

Three decades ago, heroin injecting was the most visible manifestation of illicit drug use. This is no longer the case. People who associate illicit drugs with syringes on the street may be tempted to think that the problem has been solved. Far from it.

Over the last 25 years, we have witnessed many different phases and trends. These included the HIV/AIDs epidemic, the growing use of cannabis, the discovery of hepatitis C in 1989 and the rise of synthetic and new psychoactive substances (NPS). More recently, we have seen methamphetamine being produced in industrial quantities and the increasing misuse of benzodiazepines, either diverted from therapeutic use or not medically licensed in Europe.

In addition to the issue of more substances on the market, we are confronted with polydrug use. Previously, we believed that there was no overlap between the different groups of people who use drugs. Today, we know that this is not the case and that polydrug use is commonplace.

Drug use is partly driven by the market. Eight to ten years ago, people’s choice of stimulants depended largely on where they lived and what was available. Now, we see huge changes. The problem is increasingly one of addictive behaviour. People who use drugs adapt and look for new and more potent fixes. Drug networks may be dismantled, but users gravitate elsewhere, out of sight.

A customer-centric approach

The agency, as part of its Strategy 2025, is rebalancing the centre of gravity of its activities, proactively making them more customer centric.

For many years, our task was to produce, share and disseminate data. Today, on top of this, we are being asked to provide analytical and targeted information to enable policymakers and others to take better informed decisions.

The information we collect and produce is important, but it has to be channelled to the appropriate (and often extremely busy) people in a digestible form. We try to reach our target audiences for three reasons to: identify their needs; help shape their understanding of the situation; and interact with them.

To meet these challenges, we are taking several steps. We produce shorter briefings alongside lengthier reports. Our website will include a digital platform offering personalised access. This will enable us to send automatically tailored information to specific individuals and for them to reach us when they wish.

For some years, the agency has been running an internal customer engagement project using surveys and focus groups. These help us to establish our customers’ needs and to work on co-productions. The first of these was a health and social responses guide. We are now working with harm-reduction services to provide guidance on equipment and evaluation support.

COVID-19 has reinforced this proactive trend. In the early days of the pandemic in March 2020, we messaged professional and drug user associations in Europe via social media to ask what practical and analytical help we could offer.

We received numerous replies and requests. It gave us great professional satisfaction to be able to provide practical solutions drawing on the expertise of our many partners and the agency. We organised webinars bringing together experts from different disciplines, such as treatment and harm-reduction programmes and associations of drug users.

This was a new way of working for us and far removed from our traditional practice of writing reports. We contacted people about their problems and asked how we could help, instead of simply inviting them to send us whatever information they had.

COVID-19 has highlighted some wider lessons. In particular, the importance of different response services supporting each other as they help the vulnerable – whether their focus be drugs, alcohol or homelessness. Often, organisations work only in their own clearly defined fields. But when they reach out to others and combine their expertise and missions, they can make a positive difference to individual lives. We want to build on that cooperation.

Emerging threats and risk communication

The agency would like to play a stronger role in identifying emerging threats and communicating risks. This could build on what we are already doing with our well-established EU Early-Warning System on new psychoactive substances. Potentially, it could also expand cooperation with national institutes of public health or, for example, with drug consumption rooms or pill-checking programmes in countries where these exist.

More than ever we need to articulate our work on two levels: the European level and local areas where specific threats are emerging. The latter will never reach 27 countries at the same time, but where and when they do occur, they are a damaging reality and may have a major impact on that locality.

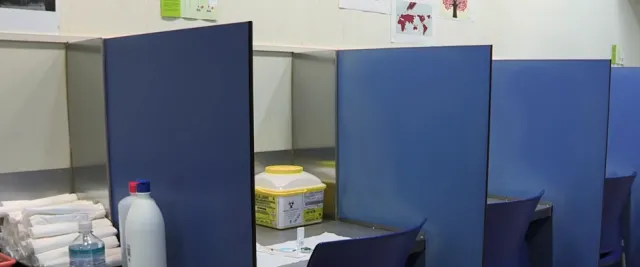

We have pilot projects studying the situation on the ground in some countries. One of these (the ESCAPE project) focuses on residues from syringes in needle-exchange programmes. While limited in coverage, this provides valuable information on drug use patterns at local level. We can cross-reference the findings with results from other indicators and ally this work with what is happening Europe-wide.

The Everywhere, Everything, Everyone motto underlines that the situation is worrying overall, and this trend is unlikely to change in the next few years. So, our approach to drugs is twofold: 1) to understand the impact of long-term trends for the health and the safety of our citizens, and 2) to detect any new threats and emerging trends far more quickly in order to prevent risks and adapt our responses (preparedness). For example, the higher availability of cocaine in the EU (long-term trend) is creating a growing crack cocaine problem at the national or city level in some Member States (local, real-time problem). Our role is to put that information and those data into a more holistic perspective to inform the policy debate and to join the dots between topics or issues that are inter-related.

We are looking to make more use of the data and our unique networks of expertise to give decision-makers and professionals the answers they need to better anticipate and respond to the challenges of today and tomorrow.

Independent external evaluators recently identified the potential for a greater role for the agency in this area. Their assessment formed part of an extremely positive evaluation, validating our work and pointing to the added value we bring. For me and my team, it is extremely gratifying and important to have been recognised so highly by outside experts.

Threat of a perfect storm

We find ourselves on the eve of the next syndemic, or let’s call it, a perfect storm. With so many substances available and the pressure of the market on consumers, there is a high risk of increased substance use and dependence in the coming years. This calls for a different, and much bigger, effort and investment in prevention programmes.

The second risk factor is the gradual unfolding of an economic crisis caused by COVID-19 and lockdowns. If governments introduce financial cuts, there will be huge consequences, especially for the disadvantaged and most socially or economically vulnerable. They will be more exposed to mental health problems and, potentially, either directly or indirectly, to activities linked to criminal gangs, such as drug trafficking and production.

The economic crisis will mean that people who take drugs may have to move to cheaper, and potentially more harmful patterns of use. Allied to this are the wider public problems of violence (frequently drug-related), the fragmentation of society and an increase in hate speech and corruption.

Do the right thing

This exhortation comes from the title of the 1989 Spike Lee film. For some, the words mean we must live together and learn how to peacefully coexist.

For me, the words mean open your eyes and see that it is time to move on. We cannot continue to look at drugs only as the old image of people who inject heroin on the street. If we do, we miss the new problems emerging in our societies. What was originally seen as a heroin epidemic problem now needs to be seen in a much broader perspective.

We have to do something. That does not mean simply putting people in prison. Law enforcement and drug control policies alone do not solve drug problems. The response has to be holistic. Policymakers, under financial pressure, must recognise this and not be tempted to cut resources to existing programmes and drug-related services.

In Europe, we are fortunate to have a balanced policy and a strong EU strategy and action plan. These reflect the EU’s basic values of human and fundamental rights. The policy is based on consensus, discussion and scientific evidence. This is why we need to invest in prevention programmes and link drug, mental health and social policies. As we prepare to weather the perfect storm, maintaining that balanced approach will be our best course of action, while reinventing our working methods and adapting them to new emerging risks and needs.

That consensus was tellingly illustrated at the special session of the United Nations General Assembly on the world drugs problem in New York in 2016. At this highly critical moment for international drug policy, the EU was totally united and spoke with one voice.

Originally, we aimed to target interested national and European decision-makers. Now our wider aim is also to provide a valuable service to professionals and practitioners in the drugs field and to the many groups and individuals on whom we rely so heavily for the input which fuels our work.

The ultimate goals my colleagues and I share, and follow in our daily work, are to contribute to society and maximise efforts to protect the public. That is the path I will follow to the end of my mandate in 2025.