Opioids: health and social responses

Introduction

This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and social responses to drug problems: a European guide. It provides an overview of the most important aspects to consider when planning or delivering health and social responses to opioid-related problems, and reviews the availability and effectiveness of the responses. It also considers implications for policy and practice.

Last update: 21 October 2021.

Contents:

Overview

Key issues

Although the prevalence of opioid dependence among European adults is low and varies considerably between countries, it is associated with a disproportionate amount of drug-related harm, which includes infectious diseases and other health problems, mortality, unemployment, crime, homelessness and social exclusion. Heroin use remains a major concern, but in many European countries the use of synthetic opioids has also been growing and, in a few now predominates. In some parts of the world, the non-medical use of opioid medications has become a major public health issue. In Europe, there are concerns that this problem may be increasing, but the available data suggests that this practice currently accounts for a relatively small share of overall opioid-related harms. This issue is explored in more detail in Non-medical use of medicines: health and social responses. In addition, New psychoactive substances: health and social responses considers the recent appearance of non-controlled synthetic opioids on the drug market in more detail.

Evidence and responses

- Pharmacological interventions, primarily opioid agonist treatment (1), usually with methadone or buprenorphine. Heroin-assisted treatment may be useful for people who have not responded to other forms of opioid agonist treatment.

- Behavioural and psychosocial interventions to address the psychological and social aspects of drug use include structured psychological therapies, motivational interventions, contingency management and behavioural therapy. These methods are often used in conjunction with pharmacological interventions.

- Residential rehabilitation involves living in a treatment facility and following a planned and structured programme of medical care, alongside therapeutic and other activities. This approach is suitable for clients with medium or high levels of need.

- Self-help and mutual aid groups and well-being interventions teach cognitive, behavioural and self-management techniques, usually without formal professional guidance.

- Recovery/reintegration support services, for example, employment and housing support.

- Harm reduction services, including needle and syringe programmes, drug consumption rooms and take-home naloxone, intended to prevent people suffering harms from opioid use including overdose.

Effective long-term treatment of opioid dependence often requires multiple treatment episodes and combinations of responses. Relapse, co-occurring mental and physical health issues and social problems are common among those with opioid dependence. Therefore, the provision of drug treatment needs to be integrated with harm reduction programmes, interventions addressing mental or physical health problems, and social support and rehabilitation services.

European picture

- People who use opioids are the largest group of those undergoing specialised drug treatment in Europe. However, differences exist between countries. These differences reflect variations in the prevalence and also in the orientation of the drug treatment systems in operation.

- The most common treatment approach is opioid agonist treatment, which is usually provided in outpatient settings. Methadone and buprenorphine are the main medications used for opioid agonist treatment in Europe. It is estimated that, overall, around 50 % of high-risk opioid users receive some form of agonist treatment, but coverage varies widely between countries.

- All European countries provide some residential treatment but the level of provision varies considerably.

Key issues: patterns of opioid use and related harms

Key questions that need to be addressed when identifying and defining a problem include who is affected, what types of substances and patterns of use are involved, and where the problem is occurring. Responses should be tailored to the particular drug problems being experienced, and these may differ between countries and over time. The wide array of factors that have to be considered at this stage in the process are discussed in the Action framework for developing and implementing health and social responses to drug problems.

For the last 40 years, injecting opioids, particularly heroin, has been perceived as the major drug problem in many European countries. Heroin is the most commonly used illicit opioid in Europe and may be smoked, injected or snorted.

The prevalence of high-risk opioid use (by injection or long duration/regular use) among adults (aged 15–64) in Europe has been relatively stable for a number of years, with estimates of users standing at around 0.35 % of the EU population. However, there is considerable variability in prevalence between countries. It should also be noted that not all countries have recent data or use the same methodological approach, and therefore estimates need to be interpreted with caution.

Although the prevalence of illicit opioid use is much lower than that of other drugs, opioids account for a disproportionate amount of drug-related harm, including:

- high rates of dependence (often associated with unemployment), criminal acts committed to obtain money to buy drugs, exposure to violence, homelessness and social exclusion;

- a relatively high risk of mortality, particularly but not exclusively, from overdoses;

- ‘open drug scenes’, with the discarding of drug paraphernalia and the prevalence of drug-related crime negatively affecting the quality of life in some communities; and

- the risk of contracting infections such as HIV, viral hepatitis and other diseases through using unclean equipment.

Overall, people who use opioids remain the largest group of those undergoing specialised drug treatment in Europe, although the share of clients in treatment they account for varies considerably between countries. Each year the use of opioids is typically reported as the main reason for entering specialised drug treatment by around 85 000 clients, or a quarter of all those embarking on drug treatment in Europe. Overcoming an individual’s dependence on opioids is usually a long-term rather than an immediate objective of treatment. For those with opioid dependence, overcoming addiction and achieving social reintegration often requires multiple treatment episodes.

Problematic opioid use is also associated with social exclusion and disadvantage, both as a risk factor and a consequence. Responses for tackling opioid dependence aim to engage dependent users in treatment as well as providing other forms of support to address their manifold psychosocial and chronic health problems and to reduce their social exclusion.

Overall, the available data suggest that new recruitment into heroin use, and especially injecting use, is lower now than in the past. Many long-term opioid users in Europe are polydrug users who are now in their 40s and 50s (see also Polydrug use: health and social responses). Long histories of injecting drug use, poor health, bad living conditions and concurrent tobacco and alcohol use make these users susceptible to chronic health problems, such as cardiovascular, liver and respiratory diseases.

Evidence and responses to opioid-related problems

Choosing the appropriate responses that are likely to be effective in dealing with a particular drug-related problem requires a clear understanding of the primary objectives for the intervention or combination of interventions. Ideally, interventions should be supported by the strongest available evidence; however, when evidence is very limited or unavailable, expert consensus may be the best option until more conclusive data is obtained. The Action framework for developing and implementing health and social responses to drug problems discusses in more detail what to bear in mind when selecting the most appropriate response options.

A wide range of services are provided to people who use drugs in European treatment settings, and provision may also vary by setting. This complexity, coupled with the generally long-term nature of treatment for opioid dependence, means that case management plays an important role in ensuring services meet the needs of each individual and that they remain engaged in treatment. Linkages to other services, such as mental health and sexual health services, are also important — see Spotlight on… Comorbid substance use and mental health problems and Spotlight on… Addressing sexual health issues associated with drug use.

The primary approaches used for treating people with opioid dependence and supporting their reintegration into the community can be grouped under five headings.

- Pharmacological interventions, such as long-term opioid agonist treatment, using methadone or buprenorphine. These substances are generally provided in outpatient settings and combined with psychosocial interventions.

- Behavioural and psychosocial interventions address the psychological and social aspects of drug use and include brief interventions, structured psychological therapies, motivational interventions, contingency management and behavioural therapy.

- Residential rehabilitation involves living in treatment facilities and following a well-structured programme of medical care, alongside therapeutic and other activities. This option is suitable for clients with medium or high levels of drug-related needs. Stays can be short or long, depending on individual needs. A prerequisite for entry may be detoxification, a short-term, medically supervised intervention aimed at the reduction and cessation of substance use, with support provided to alleviate withdrawal symptoms or other negative effects.

- Self-help and mutual aid groups may teach cognitive and behavioural techniques of self-management usually without formal professional guidance. In addition, well-being interventions such as meditation, mindfulness and physical activity may be offered.

- Recovery/reintegration support services include, for example, employment and housing support.

Current evidence indicates that pharmacological treatment can be effective in keeping patients in treatment and in reducing illicit opioid use. In addition, pharmacological treatment also reduces overdose risk and mortality, as well as reported risk behaviours associated with acquiring infectious diseases.

Evidence also suggests that the effects of opioid agonist treatment and detoxification using methadone or buprenorphine (where diminishing doses are provided over a fixed time) may be enhanced by psychosocial interventions. With the inclusion of a range of appropriate support measures, these interventions can be regarded as structured therapeutic processes that address both psychological and social aspects of a client’s behaviour.

As an incentive-based treatment, contingency management has been shown to reduce the use of other drugs when provided alongside opioid agonist treatment. In the context of contingency management, clients’ behaviours are rewarded (or, less often, punished) in line with treatment objectives and adherence to, or failure to adhere to, programme rules or their treatment plan. For example, clients can be rewarded with vouchers that can be exchanged for retail items.

Other general types of psychosocial intervention that have been used to treat people who use drugs include cognitive behavioural therapy and motivational interviewing. Cognitive behavioural therapy interventions promote the development of alternative coping skills and focus on changing behaviours and cognitions related to substance use through training that emphasises self-control, social and coping skills and relapse prevention. Motivational interviewing seeks to harness an individual’s motivation to engage with the treatment process.

Effective long-term treatment for opioid dependence often requires multiple treatment episodes and combinations of responses. For example, opioid agonist treatment generally involves long-term outpatient pharmacological maintenance, typically in combination with psychosocial interventions and regular medical contacts to manage psychiatric comorbidity, treat infectious diseases associated with injecting drug use and produce improvements across a range of other health and social outcomes.

Some studies have suggested that for a small minority of people with chronic heroin use problems who have repeatedly failed to respond successfully to other interventions, the provision of heroin-assisted treatment may be an appropriate option to consider. Evidence indicates that, for these clients, prescribed heroin along with flexible doses of methadone can increase retention in treatment and may improve other treatment outcomes. Caution is needed though, as evidence also suggests that such interventions may have an increased risk of adverse events (that is, harm caused to a patient as a result of the treatment intervention).

The quality of treatment delivery is important, and this includes prescribing adequate doses of opioid agonist medications, as this has been shown to prevent people from taking heroin or other opioids on top of their prescription and to increase retention in treatment. It is recommended that doses are directly supervised in the early stages of treatment, particularly for methadone, to avoid the risk of diversion, but that takeaway doses should nevertheless be provided when the benefits from a reduced number of visits to treatment facilities outweigh this risk (see Non-medical use of medicines: health and social responses). New modes of opioid agonist treatment delivery may facilitate access to treatment and increase retention, such as take-home formulations or slow-release formulations of buprenorphine that potentially allow clients to have sustained opioid agonist treatment with a single monthly injection.

Continuity of care and managing discharge are also important, as the period immediately after leaving treatment, whether because of drop-out, discharge or transfer between services (e.g. on release from prison) is associated with a higher risk of overdose. Similarly, to sustain good outcomes over the longer term, those in opioid agonist treatment may benefit from a range of additional measures, such as relapse prevention and help with social reintegration, including training, employment and housing support.

In response to COVID-19-related challenges, services have introduced a range of measures to ensure continuity of care, including the use of telemedicine approaches. However, it is still too early to comment on the effectiveness of these methods.

Harm reduction services, such as needle and syringe programmes, drug consumption rooms, testing for drug-related infectious diseases and providing take-home naloxone, can also play an important role in engaging people with the available services and preventing opioid-related harms, including overdose. These approaches are discussed in more detail in Drug-related infectious diseases: health and social responses.

Overview of the evidence on … treating opioid dependence

| Statement | Evidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Effect | Quality | |

|

Opioid agonist treatment keeps patients in treatment and reduces illicit opioid use. Its effect may be enhanced by psychosocial support. |

Beneficial |

High |

|

When detoxification is indicated, tapered doses of methadone or buprenorphine should be used in combination with psychosocial interventions. |

Beneficial |

High |

|

Opioid agonist treatment reduces mortality. |

Beneficial |

Moderate |

|

For people with chronic heroin use who have not responded to other treatments, prescribing heroin along with flexible doses of methadone increases retention and may improve other outcomes. However, this option may carry an increased risk of adverse events. |

Beneficial |

Moderate |

|

Providing an incentive-based treatment approach such as contingency management to people on opioid agonist treatment can reduce the use of other drugs such as cocaine. |

Beneficial |

Moderate |

Evidence effect key:

Beneficial: Evidence of benefit in the intended direction. Unclear: It is not clear whether the intervention produces the intended benefit. Potential harm: Evidence of potential harm, or evidence that the intervention has the opposite effect to that intended (e.g. increasing rather than decreasing drug use).

Evidence quality key:

High: We can have a high level of confidence in the evidence available. Moderate: We have reasonable confidence in the evidence available. Low: We have limited confidence in the evidence available. Very low: The evidence available is currently insufficient and therefore considerable uncertainty exists as to whether the intervention will produce the intended outcome.

European picture: availability of opioid-related interventions

Most treatment for people with opioid dependence in Europe is provided on an outpatient basis, most commonly in specialist drug services. Low-threshold services, generic healthcare and mental healthcare, and general practitioners all play an important role in some countries. Inpatient care is less common but still remains important in terms of the numbers treated, with psychiatric hospitals, therapeutic communities and specialised residential treatment centres all utilised for this purpose.

Opioid agonist treatment

It is estimated that around 50 % of opioid-dependent persons in Europe receive some form of agonist treatment. National estimates, where available, vary widely, from about 10 % to around 80 %, highlighting both the heterogeneous situation found in Europe with respect to treatment coverage and the fact that treatment provision remains insufficient in many parts of Europe, despite improvements in a number of countries. Also over the last decade, many countries have observed an overall increase in the age of those receiving opioid agonist treatment. Careful planning is needed to meet the future needs of the ageing cohort of opioid users seen in many countries in Europe, including specialised nursing homes for long-term residential care.

Methadone and buprenorphine-based medications are the most commonly prescribed opioid agonist medicines in Europe. Limited use is also made of other substances, such as slow-release morphine (the main opioid agonist medication used in Austria) or diacetylmorphine (in heroin-assisted treatment), which together are estimated to be prescribed to around 3 % of those in opioid agonist treatment. Heroin-assisted treatment is available in a small but growing number of European countries.

Research conducted in 12 European countries explored factors that may limit the adequate availability of opioid medicines, including those used for the treatment of opioid dependence. Legal and regulatory barriers, restrictive policies, limited knowledge and negative attitudes, as well as narrow inclusion criteria and high costs, were all reported as potential barriers to achieving adequate levels of treatment provision. Major obstacles to improving access to care in some countries included restrictions on the number of medical practitioners allowed to prescribe opioid agonist medications or the number of pharmacies permitted to dispense these products.

Residential treatment

In most European countries, residential treatment programmes, such as therapeutic communities, are an important element of treatment and rehabilitation for people who use opioids.

The term ‘residential treatment’ encompasses a range of treatment models, where those with drug problems live together as a therapeutic unit, usually either in the community or in a hospital setting (see box on therapeutic communities). Historically these approaches have tended to be abstinence-oriented, although there is now also a growing interest in integrating opioid agonist treatment into these settings. Evidence-based clinical guidelines and service standards for quality assurance in residential treatment have been established in most countries where this approach is commonly used. The therapeutic approaches used in residential treatment settings commonly include the use of 12-step or Minnesota models and cognitive behavioural interventions.

The level of residential treatment provision differs between countries, with more than two-thirds of the facilities in Europe found in just six countries, and Italy accounting for the highest number of these.

Implications for policy and practice

Basics

- The core intervention is opioid agonist treatment. This has been shown to be an effective way to reduce illicit opioid use and mortality.

- Different medications are available for agonist treatment. Therapeutic choices should be based on individual needs, involve a dialogue with patients and be subject to regular review.

- Abstinence-oriented psychosocial treatment in residential settings can benefit some opioid-dependent people if they remain in treatment.

Opportunities

- Optimise service delivery: the quality of treatment delivery is important; in particular it is vital to ensure that adequate doses of opioid agonist medications are prescribed, as well as maintaining continuity of care and links to other health and social support services. Increasing access to opioid agonist treatment should remain a public health priority in those countries where it falls below recommended levels.

- Where good coverage has been achieved and many of those in opioid agonist treatment have now been receiving care for many years, there may be a need to review individual therapeutic goals, to promote recovery where appropriate, and to increase the attention given to social reintegration, including employment.

- Careful planning is needed to meet the future needs of the ageing cohort of opioid users, seen in many countries in Europe, including specialised nursing homes for long-term residential care.

- New formulations of medications are in development, including slow-release products, that may increase the treatment options available in this area after individuals have undergone appropriate evaluation.

- Innovative low-threshold and community engagement models for opioid agonist treatment have shown promise and merit further research.

Gaps

- Treatment services should be alert to the use of opioids other than heroin as well as to polysubstance use (including alcohol and tobacco) among treatment entrants.

- Better information on unmet needs for treatment is required in order to ensure appropriate levels of service availability.

- Improved monitoring is required of the role played by medicinal opioids and/or novel or non-controlled synthetic opioids in Europe’s drug problem.

- There is scope in many countries to increase the screening for opioid problems and to offer appropriate treatment in the criminal justice system in general, and within the prison setting in particular.

- Research is needed on how to improve retention in treatment for people in opioid agonist treatment.

Data and graphics

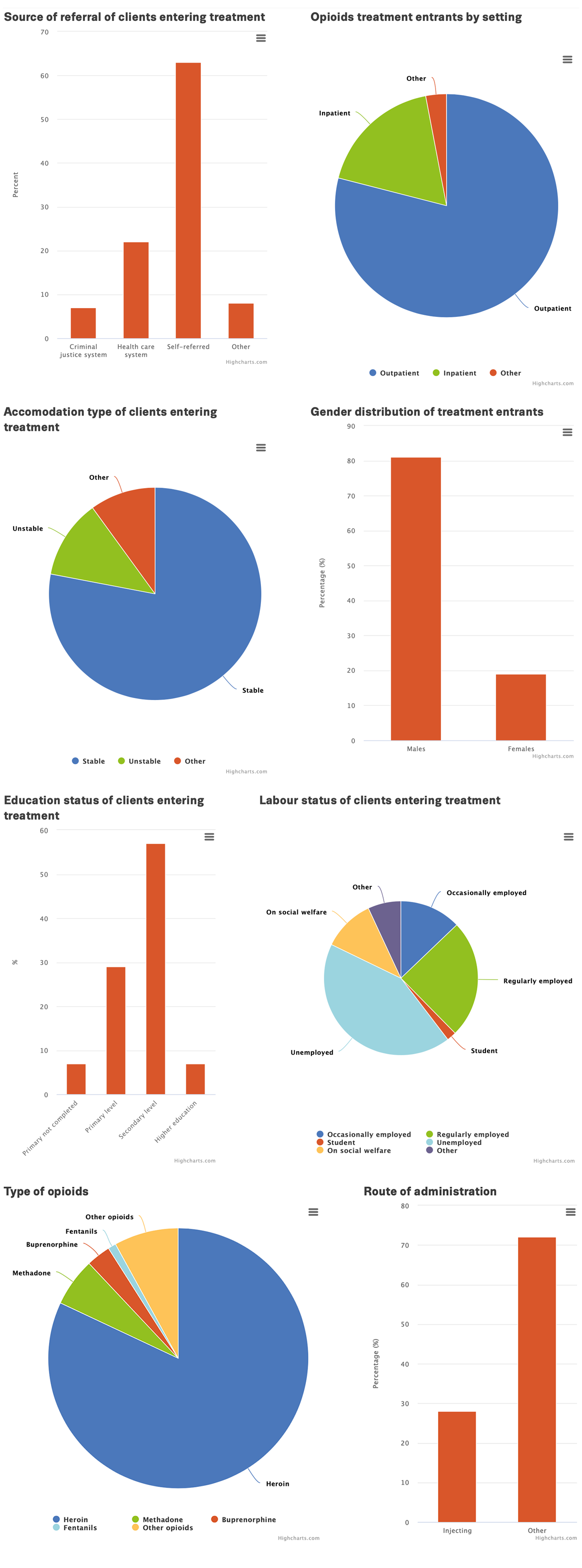

In this section, we presents some key statistics on the prevalence of high-risk opioids use among all adults (15-64), as well as clients entering treatment for opioids in the EU-27, Norway and Turkey. For more detailed statistics please refer to the Data section of our website. To view an interactive versions of the infographic below, as well as to access its source data, click on an the infographic.

Further resources

EMCDDA

- Best Practice Portal.

- EMCDDA resources on heroin.

- Balancing access to opioid substitution treatment (OST) with preventing the diversion of opioid substitution medications in Europe: Challenges and implications, EMCDDA Paper, 2021.

- European drug report 2021: trends and developments.

- Recovery, reintegration, abstinence, harm reduction: the role of different goals within drug treatment in the European context, Background paper, Annette Dale-Perera, 2017.

- Pregnancy and opioid use: strategies for treatment, EMCDDA Paper, 2014.

- Residential treatment for drug use in Europe, EMCDDA Paper, 2014.

- Therapeutic communities for treating addictions in Europe: evidence, current practices and future challenges, Insights, 2014.

Other sources

- ATOME (Access to opioids medications in Europe) project, Final report summary, 2014.

- World Health Organization, Guidelines for identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy, 2014.

- World Health Organization, Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence, 2009.

- Louisa Degenhardt, PhD Prof Jason Grebely, PhD Jack Stone, PhD Prof Matthew Hickman, PhD Prof Peter Vickerman, PhD Brandon D L Marshall, PhD et al., Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32229-9, 2019

About this miniguide

This miniguide provides an overview of what to consider when planning or delivering health and social responses to problems related to opioids, and reviews the available interventions and their effectiveness. It also considers implications for policy and practice. This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and social responses to drug problems: a European guide.

Recommended citation: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2021), Opioids: health and social responses, https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/mini-guides/opioids-health-an…

Identifiers

HTML: TD-06-21-024-EN-Q

ISBN: 978-92-9497-673-4

DOI: 10.2810/273937

(1) The term opioid agonist treatment is used here as preferred language to cover a range of treatments that involve the prescription of opioid agonists to treat opioid dependence. The reader should be aware this term includes opioid substitution treatment (OST), which may still be used in some of our data collection tools and historical documents.