Cannabis: health and social responses

Introduction

This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and social responses to drug problems: a European guide. It provides an overview of the most important aspects to consider when planning or delivering health and social responses to cannabis-related problems, and reviews the availability and effectiveness of the responses. It also considers implications for policy and practice.

Last update: 6 July 2023.

Contents:

Overview

Key issues

Cannabis is the most widely used illicit drug in Europe and globally. As well as herbal cannabis and cannabis resin, an increasing range of more novel forms of the drug may now be observed on the illicit market. In addition, a variety of commercial products containing extracts from the cannabis plant, but low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), have appeared in many countries. Regulatory responses are also becoming more variable and complicated, as several countries permit cannabis products to be available under certain circumstances for therapeutic purposes, and some are proposing the tolerance of some forms of recreational consumption. Therefore, while most health and social concerns still remain focused on illicit cannabis consumption, this is becoming a more complex area from both a definitional and response perspective.

Cannabis use can result in, or exacerbate, a range of physical and mental health, social and economic problems. Such problems are more likely to develop if use begins at a young age and develops into regular and long-term use. The primary objectives for health and social responses that address cannabis use and its associated problems should therefore include:

- preventing use, or delaying its onset from adolescence until young adulthood;

- preventing the escalation of cannabis use from occasional to regular use;

- reducing harmful modes of use; and

- providing interventions, including treatment, for people whose cannabis use has become problematic.

Response options

- Prevention programmes such as multicomponent school interventions that develop social competences and refusal skills, as well as healthy decision-making and coping strategies and correct normative misperceptions about drug use; family interventions; and structured computer-based interventions.

- Treatment interventions, including cognitive behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing and contingency management; some web- and computer-based interventions. Multidimensional family therapy is an option for young patients.

- Harm reduction interventions, for example addressing the harms associated with smoking cannabis, especially when used together with tobacco.

European picture

- Universal prevention is in widespread use but the approaches adopted do not always reflect the evidence base in this area. Well-designed school-based prevention programmes have been shown to reduce cannabis use. Selective prevention approaches are used in some European countries, most commonly with young offenders or with youth in care institutions, but little is known about their effectiveness. Indicated prevention approaches and brief interventions do not appear to be widely used.

- While some level of cannabis-specific treatment is reported to be available in around half the EU Member States, in many countries treatment for people who have cannabis problems is offered within generic drug treatment programmes. Treatment is generally provided in community or outpatient settings and increasingly online. However, the extent and nature of the treatment offered for cannabis-related problems is difficult to summarise at the EU level.

Key issues: patterns of cannabis use and related harms

Key questions that need to be addressed when identifying and defining a problem include who is affected, what types of substances and patterns of use are involved, and where the problem is occurring. Responses should be tailored to the particular drug problems being experienced, and these may differ between countries and over time. The wide array of factors that have to be considered at this stage in the process are discussed in the Action framework for developing and implementing health and social responses to drug problems.

Cannabis comes from the flowers or extract of a plant, Cannabis sativa. An increasingly wide range of cannabis products can be seen in Europe, with a variety of compositions and forms.

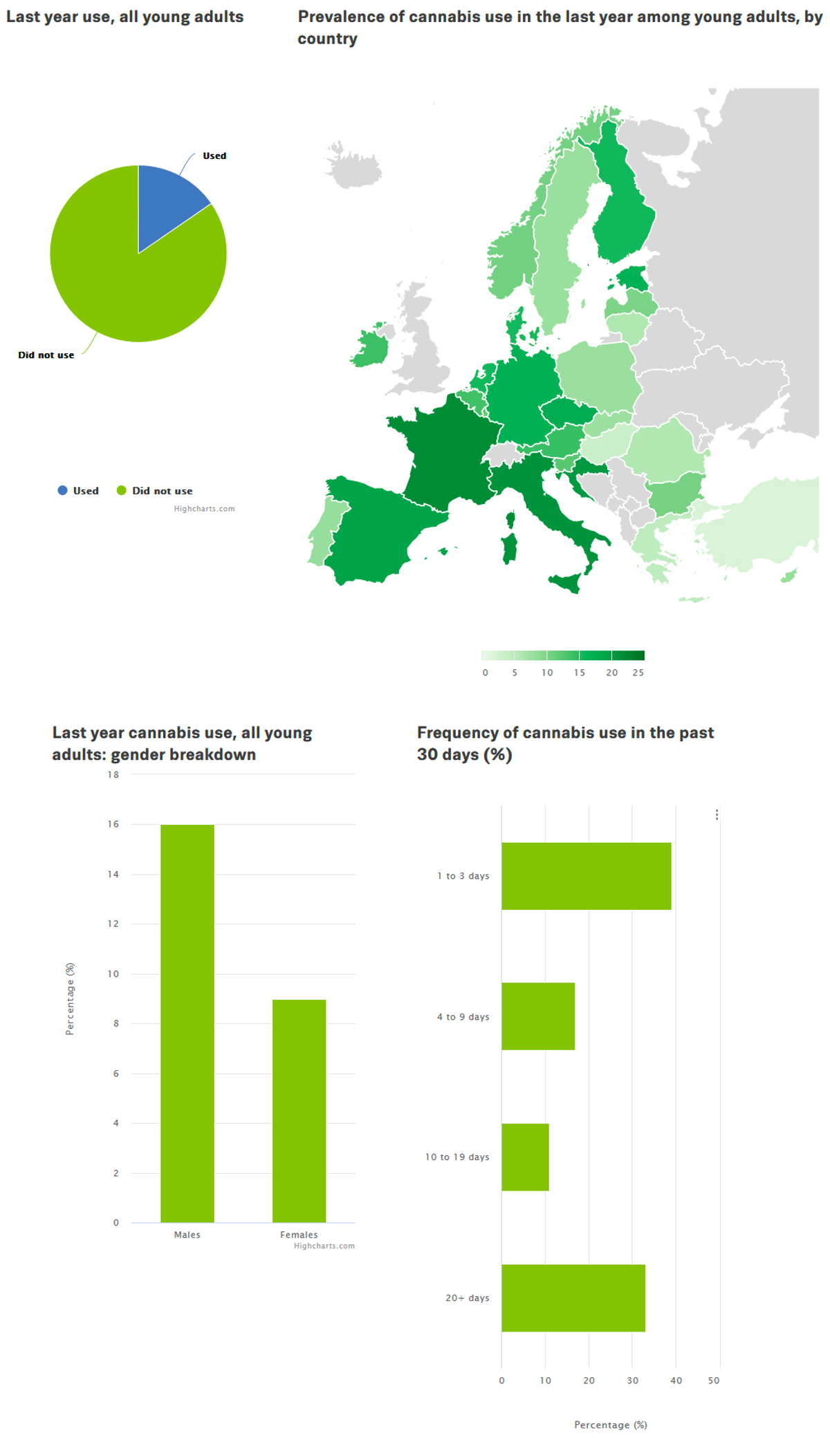

Cannabis is the most widely used illicit drug in Europe and globally. Cannabis use is highest among young adults and the age of first use of cannabis is lower than for most other illicit drugs. It is estimated that about 16 million young Europeans (aged 15–34), or around 15 % of this age group, used cannabis in the last year, with this figure increasing to around 20 % in the 15–24 age group. However, there is considerable variation in reported levels of use between countries, with prevalence rates among young adults typically ranging from 3 % to about 22 %.

Cannabis use is often experimental, commonly lasting for only a short period of time in early adulthood. However, a minority of people do develop more persistent and problematic patterns of use, with such problems being associated with regular, long-term and high-dose cannabis use. These problems can include:

- poor physical health (e.g. chronic respiratory symptoms);

- mental health issues (e.g. cannabis dependence and psychotic symptoms);

- social and economic problems arising from poor school performance, failure to complete education, impaired work performance or involvement in the criminal justice system; and

- possible adverse effects on the foetus when consumed during pregnancy.

These mental health and social and economic outcomes are more likely if regular use begins in adolescence, while the brain is still developing. The risks may increase with the use of higher potency cannabis products, especially those with high concentrations of the main psychoactive component tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). There is some evidence to suggest that concentrations of another component, cannabidiol (CBD), may mediate some of the negative effects associated with high dose THC. In addition, cannabis use sometimes causes acute symptoms that lead to presentations at hospital emergency departments. However, despite its extensive use worldwide, deaths related to cannabis use are rare.

The negative consequences for young people of incurring criminal records for use or possession offences have raised concerns in some countries that criminal penalties may be disproportionate to the harms caused by cannabis use itself. This is one of the factors driving experimentation with different regulatory models in this area.

In Europe, the most common method of using cannabis still appears to be smoking it mixed with tobacco. This brings additional health risks, while the associated nicotine dependence may also make treatment more difficult. It also points to the need for a more holistic consideration of policies and responses relating to cannabis and tobacco.

Driven, at least in part, by the introduction of new models of cannabis regulation, in recent years there has been a rapid growth in both the range of available products based on cannabis and the modes of use. Capsules, oils, a range of different edibles and vaporisers are increasingly available. These new products and modes of use, although potentially preferable to smoking cannabis with tobacco, may bring different risks. For example, edibles may pose greater risk of overdose, including accidentally by young children attracted to products such as cakes, sweets and chocolate. Also, the use of highly concentrated extracts via ‘dabbing’ appears to be associated with significant adverse health effects. There are many types of vaporiser, which may be used with a variety of cannabis extracts and products and as a result may have different risks. The 2019–2020 outbreak of severe lung injury in North America

Concerns have also been growing about problems associated with highly potent synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, commonly referred to as synthetic cannabinoids. Despite acting on the same cannabinoid receptors in the brain, these substances are very different from cannabis and their use may be associated with more severe consequences, including death. They are discussed in New psychoactive substances: health and social responses.

The primary objectives for health and social responses to address cannabis use and associated problems may include:

- preventing use or delaying its onset from adolescence until young adulthood;

- preventing the escalation of cannabis use from occasional to regular use;

- reducing harmful modes of use;

- providing treatment for people whose cannabis use has become problematic; and

- reducing the likelihood of people driving after consuming cannabis or engaging in other activities where cannabis intoxication may increase the risk of accidents.

Policymakers might also want to consider how to reduce the involvement of young people who use cannabis in the criminal justice system. In addition, where forms of cannabis are being made available legally, ensuring product safety and enforcing regulatory safeguards, such as the prevention of sales to minors, will be important considerations.

Evidence and responses to cannabis-related problems

Choosing the appropriate responses that are likely to be effective in dealing with a particular drug-related problem requires a clear understanding of the primary objectives for the intervention or combination of interventions. Ideally, interventions should be supported by the strongest available evidence; however, when evidence is very limited or unavailable, expert consensus may be the best option until more conclusive data is obtained. The Action framework for developing and implementing health and social responses to drug problems discusses in more detail what to bear in mind when selecting the most appropriate response options.

Prevention

Prevention programmes that have shown evidence of being effective in relation to cannabis use generally take a developmental perspective and are not substance-specific. Prevention programmes for adolescents often aim to reduce or delay cannabis use along with the use of alcohol and cigarettes.

Well-designed school-based prevention programmes have been shown to reduce cannabis use. Such programmes are manual-based (that is their implementation is standardised through the use of protocols and manuals for those delivering them) and generally have multiple aims: to develop social competences and refusal skills; to improve decision-making and coping; to raise awareness of the social influences on drug use; to correct normative misperceptions that drug use is common among peers; and to provide information about the risks involved in using drugs. School-based programmes that focus solely on increasing students’ knowledge of the risks of drug use have been found to be ineffective in preventing cannabis and other drug use. Examples of evidence-based interventions carried out in schools to prevent cannabis use among adolescents include the Sobre Canyes i Petes programme, an initiative found to be potentially beneficial in preventing progression from non-use or ever-use of cannabis to regular cannabis use; and Unplugged, which was found to be beneficial in preventing the use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. For examples of other positively evaluated programmes see the Best practice portal – Xchange prevention registry.

Prevention programmes that are delivered across multiple settings and domains (e.g. in school, to the family, in the community) appear to be the most effective.

Standalone mass media campaigns (including TV, radio, print and internet) that use social marketing principles and disseminate information about the risks of drug use tend to be evaluated as ineffective with respect to behavioural change. It is therefore generally recommended that they should only be considered as part of a wider set of programmes that incorporate a broader range of approaches, and are also carefully evaluated.

Brief interventions generally aim to reduce the intensity of drug use or prevent its escalation to problem use. These interventions are time-limited, and targeting and delivery methods vary considerably. Part of the attraction of this approach is that it may be used in different settings, for example, by general practitioners, counsellors, youth workers or police officers, as well as in treatment centres. This type of intervention mainly incorporates elements of motivational interviewing. Recent reviews found that, while they have some effects on alcohol use, they do not reduce cannabis use and further studies are required.

There are an increasing number of studies assessing the effectiveness of digital interventions and there is promising but still limited evidence that structured interventions delivered via computers and the internet may help prevent cannabis use.

Overview of the evidence on … interventions to prevent or delay cannabis use

| Statement | Evidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Effect | Quality | |

| Multicomponent interventions can reduce cannabis use when delivered in schools using social competence and influence approaches, correcting normative misperceptions and developing social competences and refusal skills. | Beneficial | High |

| Digital interventions increase the accessibility to programmes and the reach of people who may be using cannabis | Beneficial | Low |

| Standalone school interventions, knowledge-based or solely based on social influence models, do not reduce cannabis use (more than usual curricula). | Unclear | Moderate |

| Digital prevention interventions may reduce cannabis use | Unclear | Low |

| Brief interventions (e.g. motivational interviewing) may produce either very small or no benefits in reducing cannabis use among young adults who are not already involved in regular illicit drug use. | Unclear | Low |

| Brief interventions delivered in schools do not have a significant effect on cannabis use | Unclear | Moderate |

Evidence effect key:

Beneficial: Evidence of benefit in the intended direction. Unclear: It is not clear whether the intervention produces the intended benefit. Potential harm: Evidence of potential harm, or evidence that the intervention has the opposite effect to that intended (e.g. increasing rather than decreasing drug use).

Evidence quality key:

High: We can have a high level of confidence in the evidence available. Moderate: We have reasonable confidence in the evidence available. Low: We have limited confidence in the evidence available. Very low: The evidence available is currently insufficient and therefore considerable uncertainty exists as to whether the intervention will produce the intended outcome.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction for cannabis use has received less attention than for other substances but is nevertheless important. Abstaining from use is the most effective way of avoiding the risks of cannabis use, and this is particularly important for children and adolescents. However, for those who choose to use cannabis, harm reduction interventions may focus on avoiding more problematic consumption patterns, limiting consumption and raising awareness of the need for vigilance against the possible negative impacts of use on other areas of life, for example, school performance or social relationships. A review of the literature undertaken to update Low Risk Cannabis Guidelines for Canada (Fischer et al, 2021) provides relevant evidence-based recommendations. This and a number of other guidelines that have recently been developed highlight the following key areas for reducing the risks involved in cannabis use.

Addressing the specific harms associated with smoking cannabis, especially in combination with tobacco, is an important but neglected topic. Interventions in this area would focus on encouraging alternative routes of administration that do not involve smoking or the use of tobacco, and limiting harm from inhalation.

Alternatives to smoking, such as vaporisers or edibles, are available, although these methods are not risk-free. The use of edibles eliminates respiratory risks but the delayed onset of a psychoactive effect may result in people taking larger than intended doses and experiencing acute adverse reactions. There is little evidence on which to judge the potential relative benefits or harms of some of the established and new technologies in this area. However, as indicated above, use of some types of vaporisers can be associated with significant health risks, particularly where highly concentrated extracts are used. Nevertheless, it is clear that from a public health point of view the co-use of tobacco with cannabis should be avoided.

Smoking practices, such as ‘deep inhalation’ and breath-holding, which are commonly used when smoking cannabis, increase the intake of toxic material into the lungs. People who use cannabis should be encouraged to avoid these practices.

The diversity of cannabis products increases the importance of users understanding the impact of variations in the nature and composition of these substances. Products with a higher THC content are associated with an increased risk of developing acute and chronic problems. There is some experimental evidence to suggest that CBD may moderate the psychoactive and potentially adverse effects of THC, so the use of cannabis containing lower THC and higher CBD levels might be preferable. Some people, for a variety of reasons such as lower costs and concerns about testing, may substitute synthetic cannabinoids for cannabis. However, these synthetic versions are variable in content and act differently to cannabis, and can also be associated with very severe acute effects, including death (see Spotlight on… Synthetic cannabinoids). A recent concern has been the emergence of cannabis products that have been adulterated with synthetic cannabinoids so that people using them may be unknowingly exposed to a variety of chemicals.

Frequent or intensive cannabis use (daily or near-daily use) is associated with a greater risk of health and social harms, so people who use cannabis should try to limit their intake as much as possible, for example using only at weekends or on one day a week.

Research suggests that driving a motor vehicle while intoxicated with cannabis increases the chance of having an accident, and this risk is likely to be considerably greater if alcohol or other psychoactive substances are also consumed. Studies indicate that people should refrain from driving (or operating dangerous machinery) for several hours after using cannabis. People who use cannabis also need to be aware of, and respect, locally applicable legal limits defining cannabis-impaired driving and recognise that THC stays in the body for a long time, and so may remain detectable in tests long after the effects have worn off.

The use of cannabis should be particularly avoided by some population groups that appear to be at higher risk of experiencing cannabis-related harm. These include adolescents, individuals with a personal or family history of psychosis or a substance use disorder, and also pregnant women, to avoid adverse effects on the foetus.

Treatment

Treatment for cannabis problems is based mainly on psychosocial approaches, including, in the case of adolescents, multidimensional family therapy. Psychosocial approaches encompass a range of structured therapeutic processes which address both psychological and social aspects of drug use behaviour. These measures vary in format, duration and intensity but include approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy, contingency management and motivational interviewing.

More specifically, the available evidence supports the use of cognitive behavioural therapies in the treatment of cannabis use and dependence in adults. Cognitive behavioural therapy promotes the development of alternative coping skills and focuses on changing behaviours related to substance use through self-control, social skills and relapse prevention training.

The available evidence also supports the use of multidimensional family therapy (MDFT) in the treatment of cannabis use among young people. MDFT is an integrated, comprehensive, family-centred method for addressing youth problems. It works with the adolescent and their family and community to improve the young person’s coping, problem-solving and decision-making skills, and to enhance family functioning.

Internet and digital-based interventions are increasingly used to reach people who currently use cannabis or may come to use in the future. There is growing evidence that they can be effective in reducing consumption and facilitating face-to-face treatment (when needed). Better-quality evidence is needed on the effectiveness of this approach.

A number of ongoing experimental studies are investigating the possible utility of pharmacological interventions for cannabis-related problems. These include the potential for using THC, and synthetic versions of it, in combination with other psychoactive medicines, including antidepressants, anxiolytics and mood stabilisers, among others. However, results to date have been inconsistent and no effective pharmacological approach to treating cannabis dependence has yet been identified.

For a small number of people, cannabis use may be associated with severe mental health problems. It is not uncommon for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder to receive an additional diagnosis of cannabis dependence, and cannabis is one of the most commonly used substances by individuals with psychosis. It is important that mental health and substance misuse services recognise these cases and ensure appropriate interventions are provided. People with psychotic disorders should avoid cannabis and be counselled against its use.

Overview of the evidence on … treating problematic cannabis use

| Statement | Evidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Effect | Quality | |

| Psychosocial interventions may reduce cannabis use and related problems, with more intensive interventions (> 4 sessions over > 1 month) producing better outcomes. | Beneficial | Low |

| Digital interventions increase the accessibility to programmes and the reach of people who may be using cannabis | Beneficial | Low |

| Digital interventions may reduce cannabis use. | Unclear | Low |

| Brief behavioural interventions (e.g. motivational interviewing) have not been found to reduce cannabis use in adolescents who are already using it at problematic levels. | Unclear | Moderate |

Evidence effect key:

Beneficial: Evidence of benefit in the intended direction. Unclear: It is not clear whether the intervention produces the intended benefit. Potential harm: Evidence of potential harm, or evidence that the intervention has the opposite effect to that intended (e.g. increasing rather than decreasing drug use).

Evidence quality key:

High: We can have a high level of confidence in the evidence available. Moderate: We have reasonable confidence in the evidence available. Low: We have limited confidence in the evidence available. Very Low: The evidence available is currently insufficient and therefore considerable uncertainty exists as to whether the intervention will produce the intended outcome.

European picture: availability of cannabis-related interventions

Prevention

Manual-based universal prevention programmes aimed at developing social competences and refusal skills as well as addressing social influences and correcting normative misperceptions about drug use are reported to be a central component in national prevention strategies in around a quarter of EU countries. Evidence-based family programmes have a slightly wider availability. Other countries have prioritised different prevention approaches, for example environmental prevention measures or community approaches.

Selective prevention responses for vulnerable groups are common in almost 10 European countries. These responses address both individual behaviours and social contexts, while at the local level they often involve multiple services and stakeholders (e.g. social services, families, young people and the police). The most common target groups are young offenders, pupils with academic and social problems and youth in care institutions. Little is known about the contents of these prevention strategies and evaluations of their effectiveness are limited

Treatment

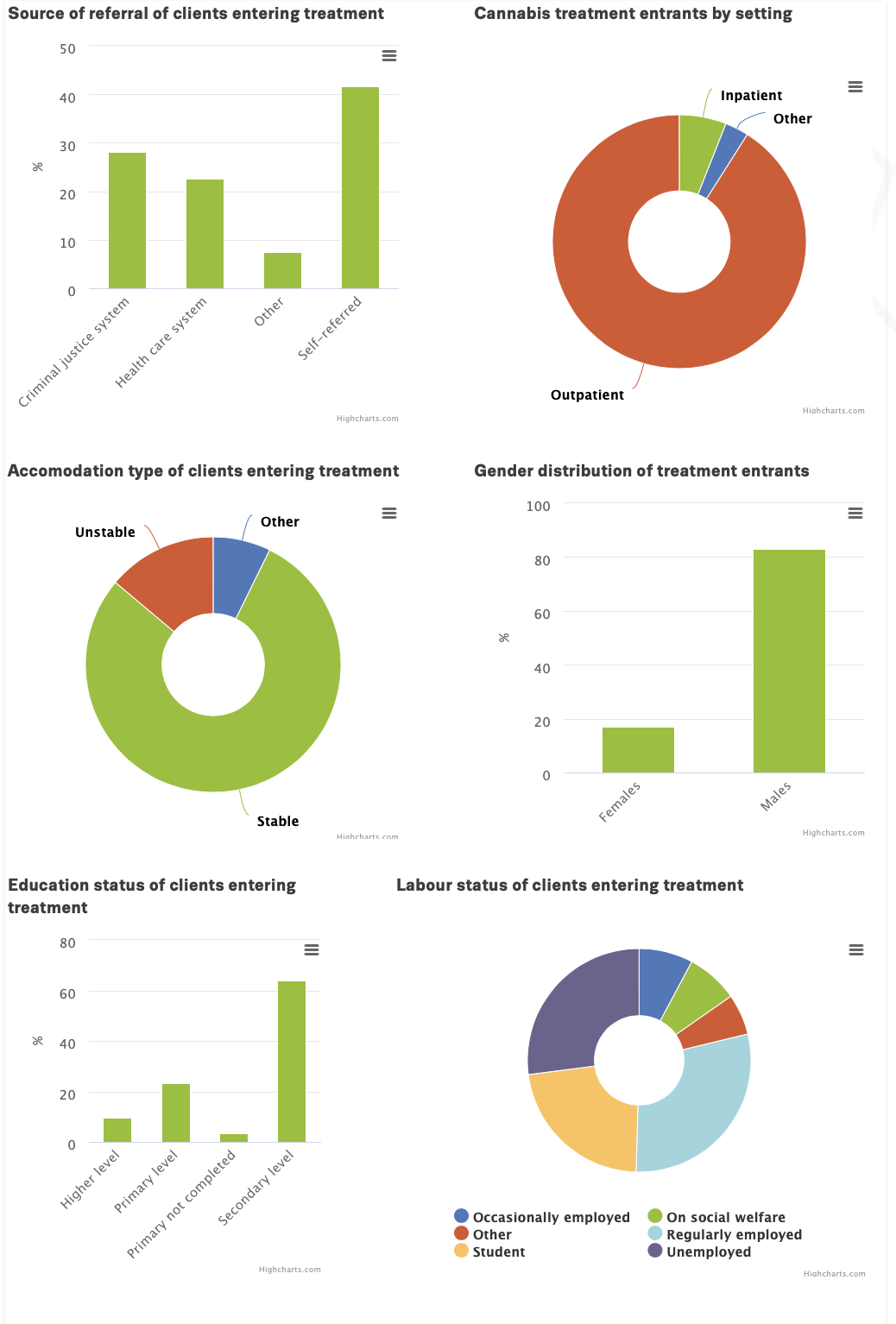

The number of first-time treatment entrants for cannabis problems in the European Union has been increasing since 2006, although more recently there are signs that the numbers may be stabilising. However, these data come from a register that may not cover treatments in all settings in some countries. In the past decade, cannabis has been the most frequently reported primary drug among new treatment clients. This rise may be due to a number of factors, including: changes in cannabis use in the general population, especially intensive use; changing risk perceptions; increasing availability of more potent cannabis products; and changes in referral practices and treatment provision. The criminal justice system has become an important source of referral for cannabis treatment, with over a quarter of people of use cannabis enter treatment for the first time in Europe being referred from the criminal justice system, while in some countries this proportion is considerably higher. The data are also influenced by differing national definitions and practices with respect to what constitutes treatment for cannabis-related disorders, which can range from a brief intervention session delivered online to admission into residential care.

Overall there is a need to develop a better understanding of cannabis treatment, including the numbers seeking help, the problems they are experiencing, the settings in which care is provided and the therapeutic responses that are offered. The data currently suggests that most cannabis treatment is provided in community or outpatient settings, but it is worth noting that around one in five people entering inpatient drug treatment report primary cannabis-related problems. The availability and coverage of treatment options for people who use cannabis differ between countries and is challenging to estimate. About half of EU countries report offering some cannabis-specific treatment, and in these countries expert opinion indicates that the majority of individuals in need of treatment for cannabis use disorders have access to treatment. A few countries report having only limited coverage, sometimes despite high overall levels of need. Less is known about the accessibility of treatment for cannabis use disorders in countries that do not offer cannabis-specific interventions. Empirical assessment of treatment coverage is particularly challenging in this area given that the extent of cannabis-related problems within the general population has not been accurately measured.

Implications for policy and practice

Basics

- Core responses in this area include general prevention approaches aimed at discouraging use or delaying onset, and providing psychosocial treatment for those with more serious problems.

Opportunities

- More attention should be paid to harm reduction approaches to cannabis use, particularly with respect to the patterns of use and co-use with tobacco.

- Greater use could be made of e-health and digital interventions alongside the evaluation of novel approaches.

- The new regulatory models for cannabis that are emerging globally can provide valuable information on the pros and cons of different options for regulation and their likely impact on responses to cannabis problems.

Gaps

- There is still a need to develop a greater awareness of the nature of cannabis-related disorders and what constitutes the most effective and appropriate treatment options for different clients.

- A better understanding of the types of treatment that people receive on entering treatment for cannabis use in Europe is required, in order to ensure that provision is appropriate and efficient.

- Greater consensus is necessary on what constitutes an appropriate way of reducing cannabis-impaired driving.

Data and graphics

In this section, we presents some key statistics on cannabis use among young people (15-34), as well as cannabis treatment in the EU-27, Norway and Turkey. For more detailed statistics as well as methodological information, please refer to the Data section of our website. To view an interactive versions of the infographic below, as well as to access its source data, click on an the infographic.

Further resources

EMCDDA

- Best practice portal – Xchange prevention registry

- Statistical bulletin.

- Low-THC cannabis products in Europe, 2020.

- European drug report 2021: trends and developments

- Monitoring and evaluating changes in cannabis policies: insights from the Americas, Technical report, 2020.

- Developments in the European cannabis market, EMCDDA paper, 2019.

- Cannabis and driving: questions and answers for policymaking, 2018.

- A summary of reviews of evidence on the efficacy and safety of medical use of cannabis and cannabinoids, Technical report, 2018.

- Cannabis legislation in Europe, 2017.

- New developments in cannabis regulation, 2017.

- Implementation of drug-, alcohol- and tobacco-related brief interventions in the European Union Member States, Norway and Turkey, Technical report, 2017.

- Treatment of cannabis-related disorders in Europe, Insights, 2015.

Other sources

- Fischer B, Robinson T, Bullen C, Curran V, Jutras-Aswad D, Medina-Mora ME, Pacula RL, Rehm J, Room R, Brink WVD, Hall W. Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines (LRCUG) for reducing health harms from non-medical cannabis use: A comprehensive evidence and recommendations update, International Journal of Drug Policy, 2021 Aug 28:103381. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103381. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34465496.

About this miniguide

This miniguide provides an overview of what to consider when planning or delivering health and social responses to cannabis-related problems, and reviews the available interventions and their effectiveness. It also considers implications for policy and practice. This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and social responses to drug problems: a European guide.

Recommended citation: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2023), Cannabis: health and social responses, https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/mini-guides/cannabis-health-a….

Identifiers

HTML: TD-06-21-025-EN-Q

ISBN: 978-92-9497-674-1

DOI: 10.2810/153521